Observing Variable Stars

Professional astronomers realized over a century ago that there were more variable stars in need of study than they could handle, so they enlisted the aid of amateur astronomers to monitor the brightness of a number of stars well suited to amateur observation: stars which changed in magnitude over a wide range and which took a long period to complete their cycle of brightness. For many years this work required no more than a telescope and a good set of charts, and such simple visual observations are still useful today, although nowadays amateurs have access to photoelectric photometers and CCD cameras which are capable of studying just about any star. The American Association of Variable Star Observers acts as a central clearing house for all sorts of amateur variable star observations, providing instruction, charts, and other support, and giving amateurs a simple online system for recording their observations.

Why observe variable stars? Mainly because it’s fun! You never know from night to night what you are going to find…remember what I said about action? No special equipment is needed other than a set of star charts which plot the variable star and give the brightness of non-variable stars around it, which are used to estimate the brightness of the variable.

If you are a deep sky observer, you already have one of essential skills of a variable star observer: you know how to locate objects in the sky. It doesn’t matter how you do it. I used traditional starhopping for several years, but now I use my Orion SkyQuest XT6’s IntelliScope setting circles to locate my variables. Once you’ve located the variable, you estimate its brightness as compared to other stars on the chart, and record the time of the observation. With a little practice you can make estimates to within a tenth of a magnitude. You can then log onto the AAVSO’s web site and enter your observation. Within ten minutes it will be moved into their database of over ten million observations, and you can see your observation on a light curve along with those of hundreds of other observers around the world. What could be neater?!

Unlike most of the observations amateur astronomers make, variable star observations have a serious side. By making a numerical estimate of the brightness of a star at a particular point in time, you are logging a piece of scientific data. The AAVSO maintains records online of every observation submitted to them over the past hundred years, keeping the records available to researchers around the world.

On a typical night, I’ll observe about a dozen stars from “my” list of about sixty stars visible at different times of year.

I keep finder charts along with the AAVSO charts in plastic sleeves in a loose-leaf binder, so that everything I need is close at hand. Since you never know ahead of time how bright a variable is going to be, you need to have a complete set of charts for each star; these can be downloaded from the AAVSO web site:

The biggest challenge in finding a variable star is that you’re looking for something that may be quite bright, or may be below the magnitude limit of your telescope, totally invisible to you. So what you look for is the star field, the pattern of stars surrounding the variable. Once you’ve found the field, you then check to see how bright the variable is. You then consult your AAVSO charts to see which stars are closest in brightness to the variable. Comparison stars on the charts are marked with their brightness to the nearest tenth of a magnitude. Because a decimal point might be confused with a faint star, they are left out, so that a 9.7 magnitude star is marked “97” and a 11.4 is marked “114” on the chart. You try to find a couple of stars, one slightly brighter than the variable, one slightly fainter, and then estimate where the variable falls between them.

Equipment for variable star observing

For visual observing as I have described above, the equipment needs are very simple. There are many variable stars within range of a pair of small binoculars, and some that can be observed with the naked eye alone. On the other hand, access to a large telescope lets you follow stars that become very faint at minimum.

I have found it advantageous to use eyepieces with a wide field of view, since they show me more of the sky at any given magnification, and let me see more comparison stars without having to move the telescope about.

My current strategy is to survey “my” variables using my Celestron 6" SCT telescope. I’ve programmed the controller with the coordinates of my variables, so I can quickly move through the list. Any variables which are currently too faint to be observable with the 6”, I revisit the next night with my larger 11” Dobsonian.

Where to start?

If you’re still not sure whether variable star observing is for you, I’d recommend reading Starlight Nights by Leslie Peltier (Sky Publishing). Peltier was the finest variable star observer of the 20th century, and his book is an entertaining introduction to a wonderful man and his love of the stars. It’s probably my very favorite astronomy book.

The AAVSO web site includes everything you need to get started. It has a complete observing manual, a list of good stars to start on, and all the charts you will need, all free of charge. Visit http://www.aavso.org

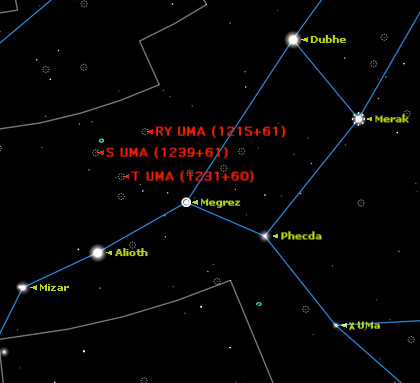

I’d recommend starting on stars that are easy to find and visible all year round, such as these stars in and around the Big Dipper: