A powers of ten journey from your backyard to the very edge of known space-time.

Read moreNight Sky Tour: The Spring Sky

The spring is a wonderful time to observe. Learn what to look for in the spring night sky tour.

Your Celestial Guidepost

The Big Dipper is a great starting point to learn your way around the night sky; in spring it's conveniently overhead. The Big Dipper itself is not an official constellation but part of a larger constellation called Ursa Major (the Great Bear). Ancient cultures saw the Big Dipper's star pattern as a bear with a long tail.

The orientation of the Big Dipper from mid-northern latitudes one hour after sunset.

The name originates from the dipper-shaped pattern formed by the seven main stars of the constellation, although observers with keen vision will see that Mizar, the second star from the end of the dipper's handle is, in fact, a double-star. Binoculars make it easier to split the pair.

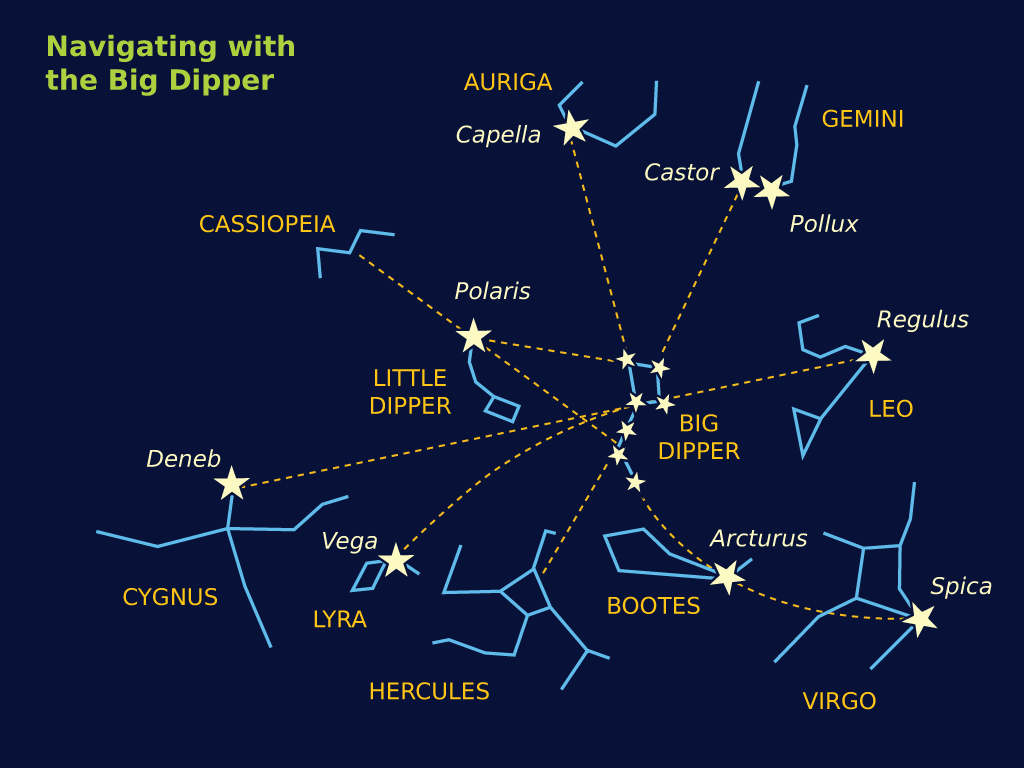

The stars of the Big Dipper serve as a handy guide to other stars and constellations. The two stars that form the front part of the dipper's bowl point straight to Polaris, the North Star, and because Polaris marks the location of the celestial north pole, the other stars in the sky seem to turn counterclockwise around it. Find Polaris and you know which way is north!

The Little Dipper and Polaris as seen from mid-northern latitudes one hour after sunset.

Polaris itself marks the end of the handle of another dipper—the Little Dipper in Ursa Minor (the Little Bear). Wrapping around Polaris is the constellation Draco. The stars that form this constellation are associated with dragons in the mythologies of many different cultures.

Earth's north pole has wandered over the millennia and so has pointed to different stars in different eras. Right now it points to Polaris, but one of Draco's stars, Thuban, was the North Star when the pyramids were built.

Arc to Arcturus...

The handle of the Big Dipper points to two of spring's brightest stars—Arcturus and Spica.

The Little Dipper and the star Arcturus as seen from mid-northern latitudes one hour after sunset.

Arcturus is the Alpha (meaning the brightest) star of the constellation Bootes (the Herdsman). Follow the arc of the handle of the Big Dipper until you come to a bright orange star. This is Arcturus, forming the point of a pattern of stars resembling a kite.

Arcturus is a giant star, twice as massive and 215 times as bright as the sun. It takes 37 years for the light of Arcturus to reach us, so when we gaze at it, we're seeing the star as it looked 37 years ago.

Ancient astromers had measured the position of Arcturus for nearly 2,000 years, which gave Edmond Halley enough data, in 1718, to discover that it was slowly moving against the background stars of its constellation. Before this discovery of proper motion, the stars were thought to be permanently fixed in the sky. Today we know that all stars move, but Arcturus moves much faster than most—about the width of the full moon every 800 years.

...and Speed on to Spica

If you keep following the arc of the handle of the Big Dipper past Arcturus, you'll encounter another bright star, Spica. Keep them straight by remembering this phrase: "Arc to Arcturus and speed on to Spica."

Polaris to Arcturus and on to Spica as seen from mid-northern latitudes one hour after sunset.

Spica resides in the constellation Virgo (the Virgin), a large zodiacal constellation that over time has represented almost every major female deity.

The Prominent Constellation of Spring

The most prominent constellation in the cool evenings of spring is Leo (the Lion).

Leo as seen from mid-northern latitudes one hour after sunset.

To find Polaris, you used the front of the bowl. To find Leo, you need to draw a line through the stars at the back of the bowl—away from Polaris. Stretch out your arm to its full length and measure about three fist-widths from Phecda—the star at the bottom of the bowl. This should put you at a point within the constellation of Leo.

Leo is a constellation of the Zodiac whose main stars have been included in many different mythologies. Stars depicting the mane and head of Leo form a pattern of stars resembling a sickle or a backward question-mark.The brightest star in Leo is Regulus, marking the end of the handle of the sickle or the dot in the question-mark. Regulus, Arcturus, and Spica are the three brightest stars of spring.

The Leonids meteor shower radiates from this constellation around mid-November.

A Beehive of Stars

To the side of Leo is the fainter constellation of Cancer (the Crab).

The Beehive Cluster in Cancer as seen from mid-northern latitudes one hour after sunset.

M44, the Beehive Cluster.

Inside the boundaries of Cancer is a group of stars neatly tucked together into a beehive shape. The Beehive Cluster (also known as Messier 44) was first described by Galileo, but it has been known since antiquity.

The beehive is easily visible to the unaided eye as a faint round patch of light. Through binoculars, it resembles a swarm of bees.

If you'd like to follow along with NASA's New Horizons Mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, please download our FREE Pluto Safari app. It is available for iOS and Android mobile devices. Simulate the July 14, 2015 flyby of Pluto, get regular mission news updates, and learn the history of Pluto.

Simulation Curriculum is the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night, SkySafari and Pluto Safari. Follow the mission to Pluto with us on Twitter @SkySafariAstro, Facebook and Instagram.

SkyWatching: Shadow Play on Jupiter

Jupiter’s rapidly moving moons constantly surprise us with their dance around the giant planet. There will be two spectacular shadow plays this week.

Jupiter’s moons are very small, even in a large telescope, but their shadows are slightly larger, and can often be seen crossing Jupiter’s face with a good amateur telescope. I’ve seen the shadows with telescopes as small as 90mm aperture, but a telescope with 6-inch or larger aperture will show them much more clearly. Steady atmospheric seeing is also essential.

If you live on the eastern seaboard, look for Jupiter just after sunset on Wednesday, May 20 around 8:10 p.m. EDT. The first thing you will notice is that only two of Jupiter’s usual four moons are visible. That’s because two of the Moons, Io and Callisto, are in front of Jupiter’s disk, and are said to be “in transit.” You probably won’t see Io, because its color and brightness blend in so well with the cloud tops behind it. You may be able to see Callisto because its dark surface stands out against Jupiter’s bright clouds. I usually see it as a tiny greyish spot. Look more closely, and you’ll see two small dark shadows on Jupiter’s face. One of these is Io’s shadow, but the other is not the shadow of Callisto. Instead it is the shadow of Ganymede, off to Jupiter’s right. That’s because of the angle at which the sun is illuminating the tableau.

On Wednesday night, May 20, the shadows of Jupiter’s moons Ganymede and Io will cross Jupiter’s face. This shows the shadows at 8:10 p.m. EDT, just after Io’s shadow has started across, and just before Ganymede’s shadow leaves. Credit: Starry Night software.

Take another look later in the evening, around 9:55 p.m., and you’ll see that Ganymede’s shadow has left the disk and that Io’s shadow is about to be hidden behind Callisto. This will be the first time I have ever seen a moon’s shadow eclipsed by another moon.

Nearly two hours later at 9:55 p.m., Ganymede’s shadow has left, and Io’s shadow is about to be eclipsed by the moon Callisto. The Great Red Spot is well placed close to Jupiter’s central meridian. Credit: Starry Night software.

Also keep a lookout for the Great Red Spot, though it is not nearly as “great” nor as “red” as it once was. It’s more usually seen as a light notch in the North edge of Jupiter’s South Equatorial Belt. At moments of steady seeing, its salmon pink color may appear briefly.

A week later on May 27, the situation nearly repeats itself, but is about two hours later, making it more easily seen across the whole of North America. Ganymede’s shadow starts across Jupiter’s face at 8:58 p.m. EDT. Io’s shadow follows at 10:01 p.m., and both shadows are present until Io’s shadow leaves at 12:18 a.m., followed by Ganymede’s at 12:34 a.m.

Exactly a week later, on Wednesday, May 27 at 10:05 p.m., the pattern repeats, except that the shadows are closer together and Callisto is no longer in front of Jupiter. Credit: Starry Night software.

Notice that at around 11:48 p.m., Io’s faster moving shadow actually passes Ganymede’s, and the two shadows merge.

At 11:48 p.m., Io’s faster moving shadow catches up with Ganymede’s, and the two shadows merge. Again, the Great Red Spot is well placed. Credit: Starry Night software.

Once again, the Great Red Spot should be in evidence.

If you live west of the Eastern time zone, be sure to subtract the appropriate corrections from the times given above: 1 hour for CDT, 2 hours for MDT, and 3 hours for PDT.

If you'd like to follow along with NASA's New Horizons Mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, please download our FREE Pluto Safari app. It is available for iOS and Android mobile devices. Simulate the July 14, 2015 flyby of Pluto, get regular mission news updates, and learn the history of Pluto.

Simulation Curriculum is the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night, SkySafari and Pluto Safari. Follow the mission to Pluto with us on Twitter @SkySafariAstro, Facebook and Instagram.

First Night Out Series: How The Stars Got Their Names

Humans have been naming the stars for millennia. The brightest stars were named long ago by people who immortalized their folklore in the heavens, and many of their names are still used today.

Centuries later, formal and systematic naming systems were developed when more extensive lists of stars were compiled.

The following sections describe in more detail how the stars received their names over the years.

Common Names

You might have heard of some of the more popular stars, such as Sirius, Betelgeuse, and Polaris. These names sound foreign, and they are—their origins are mostly Arabic translations of Latin descriptions.

Common names. Credit: Starry Night software.

But to add to the confusion, scribes in the Middle Ages reproduced astronomical manuscripts by hand—a method that introduced errors, especially when copying words they did not know. Over time, the process of making copies of copies made it harder to decipher the original meaning of some words.

The common names for the brightest stars in the sky date back to ancient myths. Stars were often named after heroes, animals, or components of the constellations they helped form. The folklore of the stars offers a tantalizing glimpse into the associations ancient peoples established with the stars.

In all, about 900 stars have common names primarily of Arabic, Greek, or Latin origin. A few star names are relatively modern, however, invented as recently as the 20th century.

A few examples of common names are Sirius (Greek for scorching), Thuban (corrupted Arabic for serpent's head), and Betelgeuse, (a copying error from yad al-jauza, meaning the hand of al-Jauza, the "Central One").

The Bayer System

Johann Bayer was a German lawyer and uranographer. He was born in Rain, Lower Bavaria, in 1572.

Common names are handy for identifying the brightest stars in the sky, but astronomers needed a system for naming all the stars in the sky, including even the faintest ones.

The Bayer system is the first of two naming systems that incorporate constellation names into the identification of stars. It names the brightest stars by assigning a Greek letter (Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and so on) in an approximate order of decreasing brightness, along with the Latin possessive name of the constellation in which the star resides.

Bayer Names. Credit: Starry Night software.

In this system, Sirius, which is in the constellation Canis Major, is known as Alpha Canis Majoris. Betelgeuse, which resides in the constellation Orion, is known as Alpha Orionis.

The ordering of stars by brightness in the Bayer system is only approximate. As an example, Rigel's name according to the Bayer system is Beta Orionis, suggesting it's the star in Orion just dimmer than Betelgeuse—but it's actually brighter. Brightness fluctuations in Betelgeuse make it brighter than Rigel at times, such as when the system was first introduced in 1603.

The Flamsteed System

John Flamsteed was an English astronomer and the first Astronomer Royal. He catalogued over 3,000 stars.

The second system that uses the constellations in which the stars reside is the Flamsteed system.

The Bayer system was useful for naming the stars—certainly better than using common names—but it had problems. The first was that of fluctuating brightness, as in the case of Betelgeuse and Rigel. The second problem was that there are only so many letters in the Greek alphabet.

Unlike the Bayer system, the Flamsteed system can be used to name an unlimited number of stars. In this system, we still use the Latin possessive name of a star's constellation, but this time the stars are distinguished not by their brightness, but also by their proximity to the western edge of their constellations.

Flamsteed Names. Credit: Starry Night software.

The star closest to the western edge is assigned the number 1; the second-closest star to the western edge is number 2, and so on.

For example, the star Sirius is called Alpha Canis Majoris in the Bayer system and 9 Canis Majoris in the Flamsteed system, meaning that it is the ninth-closest star to the western edge of the constellation Canis Major.

Catalog Names

The faintest of stars are known only by their identifiers in specialized catalogs. These catalogs can contain billions of stars, from the brightest to the very faintest, which can be seen only with powerful telescopes and long exposures.

Catalog Names. Credit: Starry Night software.

For example, Sirius is bright enough to have a poetic common name, descriptive Bayer and Flamsteed names, and the label HIP32349 in the Hipparcos catalog.

Naming Your Own Star

You may have read that you can buy a star, or invest in real estate on the moon or Mars.

Some companies provide this service to raise funds for science or a charity but others do it only to line their own pockets. Please do your research and be aware that although these companies charge you a fee for an official-looking certificate, these services have no formal validity at all. The scientific community only recognizes naming conventions based on the regulations of the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

Remember that the beauty of the night sky is not for sale, and it is free for everyone to enjoy.

If you'd like to follow along with NASA's New Horizons Mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, please download our FREE Pluto Safari app. It is available for iOS and Android mobile devices. Simulate the July 14, 2015 flyby of Pluto, get regular mission news updates, and learn the history of Pluto.

Simulation Curriculum is the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night, SkySafari and Pluto Safari. Follow the mission to Pluto with us on Twitter @SkySafariAstro, Facebook and Instagram.

The Ten Brightest Stars In The Sky

From our corner of the galaxy, these stars are the most brilliant signposts in the heavens and can be enjoyed even from the light-polluted hearts of major cities.

Sirius

All stars shine but none do it like Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky. Aptly named, Sirius comes from the Greek word Seirius, meaning, "searing" or "scorching." Blazing at magnitude -1.42, it's twice as bright as any star in our sky besides the Sun.

Sirius resides in the constellation Canis Major, the Big Dog, and is commonly called the Dog Star. In ancient Greece the dawn rising of Sirius marked the hottest part of summer—the season's "dog days."

Sirius no longer marks the hottest part of summer, because it now rises later in the year. This happens because the Earth has been wobbling slowly around its axis in a 25,800-year cycle. This wobble—called precession—is caused by the gravitational attraction of the Moon on Earth's equatorial bulge, and it gradually changes the locations of stars on the celestial sphere.

The best time to see Sirius is probably in winter (for northern-hemisphere observers), because it rises fairly early in the evening. To find the Dog Star, use the constellation Orion as a guide. Follow the three belt stars 20 degrees southeast to the brightest star in the sky. Your fist at arm's length covers about 10 degrees of sky, so it's about two fist-widths down.

Sirius, the red giant star Betelgeuse, and Procyon in Canis Minor form a popular asterism known as the Winter Triangle.

Sirius is 23 times as luminous as the Sun, and about twice the mass and diameter. At a mere 8.5 light-years away from Earth, Sirius seems so bright in part because it's the fifth-closest star to the Sun.

The brilliance of Sirius illuminates not only our night skies, but also our understanding. While observing it in 1718, Edmond Halley (of comet fame) discovered that stars move in relation to one another—a principle now known as proper motion.

This Hubble Space Telescope image shows Sirius A, the brightest star in our nighttime sky, along with its faint, tiny stellar companion, Sirius B.

In 1844, the German astronomer Friedrich Bessel observed that Sirius had a wobble, as if it were being tugged by a companion star. And in 1862, Alvan Clark solved this mystery (while testing his new 18.5-inch lens, the largest refracting telescope in the world at that time). Clark discovered that Sirius was not one star but two.

This proved to be the first discovery in what became a whole class of stars: the compact stellar remnant or white dwarf. These are stars that, once depleting all their hydrogen, collapse to a very dense core. Astronomers have calculated that Sirius's companion—dubbed Sirius B—contains the mass of the Sun in a package as small as the Earth.

Sixteen milliliters of matter from Sirius B (that is, about one cubic inch of the stuff) would weigh 2000 kilograms on Earth.

At magnitude 8.5, it is one four-hundredth as luminous as the Sun. The brighter and larger companion is now known as Sirius A.

Canopus

Canopus resides in the constellation Carina, the Keel. Carina is one of three modern-day constellations that once formed the ancient constellation of Argo Navis, named for the ship Jason and the Argonauts sailed in to search for the Golden Fleece. Two other constellations form the sail (Vela) and the stern (Puppis).

In modern odysseys, spacecraft like Voyager 2 used the light from Canopus to orient themselves in the sea of space.

Canopus is a true powerhouse. Its brilliance is due more to its great luminosity than its proximity. This number two on our list of stars has 14,800 times the intrinsic luminosity of the Sun! But at 316 light-years away, it's more than 37 times as far from us as the number one star, Sirius.

With a magnitude of minus-0.72, Canopus is easy to find in the night sky, though it is only visible at latitudes south of 37 degrees north.

To catch a glimpse of it from middle-latitude or southern locations in the United States, look for a bright star low on the southern horizon during the winter months. Canopus is 36 degrees below the brightest star in the sky, Sirius. The further south you are, the better your view will be.

Canopus is a yellow-white F super giant—a star with a temperature from 5,500 to 7,800 degrees Celsius (10,000 to 14,000 degrees Fahrenheit)—that has stopped hydrogen fusion and is now converting its core helium into carbon. This process has led to its current size, 65 times that of the Sun. If we were to replace our Sun with Canopus, it would nearly envelop Mercury.

Canopus will eventually become one of the largest white dwarfs in the galaxy and might just be massive enough to fuse its carbon, turning into a rare neon-oxygen white dwarf. These are rare because most white dwarfs have carbon-oxygen cores, but a massive star like Canopus can begin to burn its carbon into neon and oxygen as it evolves into a small, dense, and cooler object.

Canopus lost its place in the celestial hierarchy for a short time in the 1800s when the star Eta Carinae underwent a massive outburst, surpassing Canopus in brightness and briefly becoming the second-brightest star in the sky. And Eta Carinae may yet outdo even Sirius, the brightest. It is fated to become a supernova, perhaps very soon in cosmic time-terms: within a few hundred thousand years.

Alpha Centauri

Alpha Centauri (or Rigel Kentaurus, as it is also known) is actually a system of three stars gravitationally bound together. The two main stars are Alpha Centauri A and Alpha Centauri B. The tiniest star in the system is Alpha Centauri C, a red dwarf.

The Alpha Centauri system is a special one. At an average distance from us of 4.3 light-years, these stars are our nearest known stellar neighbors.

A comparison of the sizes and colors of the stars in the Alpha Centauri system with the Sun.

Centauri A and B are remarkably Sun-like, with Centauri A a near twin of the Sun (both are yellow G stars). In comparison to the Sun, Alpha Centauri A is 1.5 times as luminous and shines at magnitude -0.01 while Alpha Centauri B is half as luminous and shines at magnitude 1.3.

Alpha Centauri C is one seven-thousandth as bright and shines at eleventh magnitude.

Of the three stars, the smallest is the closest to the Sun, 4.22 light-years away. Because of its proximity, it is known as Proxima Centauri.

When night falls and the skies are clear in summer, the Alpha Centauri system shines at a magnitude of minus-0.27, low in the southern sky. You can find it at the foot of the Centaur in the constellation Centaurus.

Because of its position in the sky, the Alpha Centauri system is not easily visible in much of the northern hemisphere. An observer must be at latitudes south of 28 degrees north (or roughly from Naples, Florida and locations further south) to see the closest stellar system to us.

The two brighter components of the system make a wonderful double star to observe in a small telescope.

Naked-eye Alpha Centauri appears so bright because it is so close. This also means that it has a large proper motion—the drifting of stars relative to each other due to their actual movements in space. In another 4,000 years, Alpha Centauri will have moved near enough to Beta Centauri for the two to form an apparent double star.

Arcturus

Arcturus is the brightest star in the northern celestial hemisphere. (The first three stars on this list are actually in the southern celestial sphere, though seasonally they are visible from the northern hemisphere of Earth).

Known as the Bear Watcher, Arcturus follows Ursa Major, the Great Bear, around the north celestial pole. The name itself derives from the Greek word arktos, meaning bear.

Arcturus is an orange giant, twice as massive and 215 times as bright as the Sun. It takes 37 years for the light of Arcturus to reach us, so when we gaze upon it, we are seeing the star as it looked 37 years ago. It glows at magnitude -0.04 in our night sky.

A variable star, Arcturus is in the last stages of life.

During its internal struggle between gravity and pressure, Arcturus has swelled to 25 times the Sun's diameter.

Eventually the outer envelope of Arcturus will peel away as a planetary nebula, similar to the famed Ring Nebula (M57) in Lyra. The star left behind will be a white dwarf.

Arcturus is the alpha (meaning brightest) star of the springtime constellation Bootes, the Herdsman. You can find it by using the Big Dipper as your celestial guidepost. Follow the arc of the handle until you come to a bright orange star. This is Arcturus, forming the point of a pattern of stars resembling a kite.

In the spring, if you keep following the arc, you'll encounter another bright star, Spica. (Keep it straight by remembering the phrase: "Arc to Arcturus, speed on to Spica.")

In the 1930s, astronomers were busy measuring the distance to nearby stars and determined—incorrectly, it turned out—that Arcturus was 40 light-years from Earth. During the 1933 World's Fair in Chicago, the light from Arcturus was collected with new photocell technology and used to activate a series of switches. Light believed to have originated at the time of the previous Chicago World's Fair 40 years earlier was used to illuminate and officially open the fair in 1933.

The science of astronomy progresses, and we now know that Arcturus is only 37 light-years away.

Vega

The name Vega comes from the Arabic word for "swooping eagle" or "vulture." Vega is the luminary of Lyra, the Harp, a small but prominent constellation that is home to the Ring Nebula (M57) and the star Epsilon Lyrae.

The ring is a luminous shell of gas resembling a smoke ring or a doughnut that was ejected from an old star. Epsilon Lyrae appears to the naked eye as a double star, but through a small telescope you can see that each of the two individual stars is itself a double! Epsilon Lyrae is popularly known as the "double double."

Vega is a hydrogen-burning dwarf star, 54 times as luminous and 1.5 times as massive as the Sun. At 25 light-years away, it is relatively close to us, shining with a magnitude of 0.03 in the night sky.

In 1984, a disk of cool gas surrounding Vega was discovered—the first of its kind—extending 70 AU from the star, roughly the distance from our Sun to the edge of the Kuiper Belt. This discovery's important because a similar disk is theorized to have played an integral role in planet development within our own solar system.

Astronomers also found a "hole" in the Vega disk, indicating the possibility that planets might have already coalesced and formed around the star. This led the astronomer and author Carl Sagan to choose Vega as the source of advanced alien radio transmissions in Contact, his first science-fiction novel. (In real life, no such transmissions have ever been detected.)

Together with the bright stars Altair and Deneb, Vega forms the popular Summer Triangle asterism that announces the beginning of summer in the northern hemisphere. The asterism crosses the hazy band of the Milky Way, which is split in two near Deneb by a large dust cloud called the Cygnus Rift.

This area of the sky is ideal for sweeping with binoculars of any size in dark-sky conditions.

Vega was the first star to be photographed, on the night of July 16, 1850, by the photographer J.A. Whipple. With the daguerreotype camera used at the time, he made an exposure of 100 seconds using a 15-inch refractor telescope at Harvard University. Fainter stars (those of second magnitude and dimmer) would not have registered at all using the technology of the time.

Vega used to be the North Star, but 12,000 years of Earth's precession has altered its place in the celestial sphere. In another 14,000 years, Vega will be the North Star again.

Capella

Capella is the primary star in the constellation Auriga (the Charioteer), and the brightest star near to the north celestial pole.

Capella is actually a fascinating star system of four stars: two similar class-G yellow-giant stars and a pair of much fainter red-dwarf stars. The brighter yellow giant, known as Aa, is 80 times as luminous and nearly three times as massive as the Sun. The fainter yellow giant, known as Ab, is 50 times as luminous as the Sun and two-and-a-half times as massive. The combined luminosity of the two stars is the equivalent of about 130 Suns.

The Capella system is 42 light-years away, its light reaching us with a magnitude of 0.08.

It is highest in the winter months and circumpolar (meaning it never sets) at latitudes higher than 44 degrees north (or roughly north of Toronto, Canada).

To locate it, follow the two top stars that form the pan of the Big Dipper across the sky. Capella is the brighter star in the irregular pentagon formed by the stars in the constellation Auriga.

South of Capella is a small triangle of stars known as the Kids. One of the most ancient legends had Auriga as a goat herder and patron of shepherds. The brilliant golden yellow Capella was known as the "She-Goat Star." The nearby triangle of fainter stars represents her three kids.

Both yellow giants are dying, and will eventually become a pair of white-dwarf stars.

Rigel

On the western heel of Orion, the Hunter, rests brilliant Rigel. In myth, Rigel marks the spot where Scorpio, the Scorpion, stung Orion after a brief but fierce battle. Its Arabic name means the Foot.

Rigel is a multiple-star system. The brighter component, Rigel A, is a blue supergiant that shines a remarkable 40,000 times stronger than the Sun! Although it's 775 light-years distant, its light shines bright in our evening skies, at magnitude 0.12.

Rigel resides in the most impressive of the winter constellations, mighty Orion. After the Big Dipper, it's the most-recognized and easiest-to-identify constellation. It helps that the shape made by Orion's stars closely matches the shape of a human hunter: three bright stars are lined up together to form a belt, the other four stars surrounding the belt compose shoulders and legs.

Telescope observers should be able to resolve Rigel's companion, a fairly bright seventh-magnitude star. But the jewel in Orion is the Great Orion Nebula (M42), a vast stellar nursery where new stars are still being born. It can be found six moon-widths south of the belt stars.

A heavy star of 17 solar masses, Rigel is likely to go out with a supernova-sized bang one day. Or it might become a rare oxygen-neon white dwarf.

Procyon

Procyon resides in the small constellation of Canis Minor, the Little Dog. The constellation symbolizes the smaller of Orion's two hunting dogs (the other is, of course, Canis Major).

The word procyon is Greek for "before the dog," for in the northern hemisphere, Procyon announces the rise of Sirius, the Dog Star.

Procyon is a yellow-white, main-sequence star, twice the size and seven times as luminous as the Sun. Like Alpha Centauri, it appears so bright because at 11.4 light-years, it is relatively close.

Procyon is an example of a main sequence subgiant star, one that is starting to die as it converts its remaining core hydrogen into helium. Procyon is currently twice the diameter of the Sun, one of the largest stars within 20 light-years.

Canis Major can be found fairly easily east of Orion during northern-hemisphere winter. Procyon, along with Sirius and Betelgeuse, form the Winter Triangle asterism.

Procyon is orbited by a white-dwarf companion detected visually in 1896 by John M. Schaeberle. The fainter companion's existence was first noted in 1840, however, by Arthur von Auswers, who observed irregularities in Procyon's proper motion that were best explained by a massive and dim companion.

At just one-third the size of Earth, the companion dubbed Procyon B has the equivalent of 60 percent of the Sun's mass. The brighter component is now known as Procyon A.

Achernar

Achernar is derived from the Arabic phrase meaning "the end of the river," an appropriate name for a star that marks the southernmost flow of the constellation Eridanus, the River.

Achernar is the hottest star on this list. Its temperature has been measured to be between 13,000 and 19,000 degrees Celsius (24,700 and 33,700 Fahrenheit). Its luminosity ranges from 2,900 to 5,400 times that of the Sun. Shining at magnitude 0.45, its light takes 144 years to reach your eye.

Achernar is more or less tied with Betelgeuse (number ten on this list) for brightness. However, Achernar is generally listed as the ninth-brightest star in the sky because Betelgeuse is a variable whose magnitude can drop to less than 1.2, as was the case in 1927 and 1941.

For northern-hemisphere observers, Achernar rises in the southeast during the winter months and is visible only from latitudes south of 32 degrees north; those further north only see a portion of the constellation.

(For Star Trek fans, the constellation of Eridanus is also home to Epsilon Eridanus, the star around which Mr. Spock's imaginary home planet of Vulcan supposedly revolves!)

Achernar is a massive class-B star containing up to eight solar masses. It is currently burning its hydrogen into helium and will eventually evolve into a white dwarf star.

Betelgeuse

Don't let Betelgeuse's ranking as the tenth-brightest star in the sky fool you. Its distance—430 light-years—hides the true scale of this supergiant. With a whopping luminosity of 55,000 suns, Betelgeuse still shines bright in our skies at a magnitude of 0.5.

Betelgeuse (pronounced "beetle juice" by most astronomers) derives its name from an Arabic phrase meaning "the armpit of the central one."

Image from ESO's Very Large Telescope showing the stellar disk.

The star marks the eastern shoulder of mighty Orion, the Hunter. Another name for Betelgeuse is Alpha Orionis, indicating that it's the brightest star in the winter constellation of Orion. But Rigel (Beta Orionis) is actually brighter. This misclassification probably happened because Betelgeuse is a variable star (a star that changes brightness over time) and it might have been brighter than Rigel when Johannes Bayer originally categorized it.

Betelgeuse is an M1 red supergiant, 650 times the diameter and about 15 times the mass of the Sun. If Betelgeuse were to replace the Sun, all the planets out to the orbit of Mars would be engulfed!

Observe Betelgeuse and you are witnessing a star approaching the end of its long life. Its huge mass suggests that it might fuse elements all the way to iron. If so, it will blow up as a supernova that would be as bright as a crescent moon, as seen from Earth. A dense neutron starwould be left behind. The other possibility is that it might evolve into a rare neon-oxygen dwarf.

Betelgeuse was the first star to have its surface directly imaged, a feat accomplished in 1996 with the Hubble Space Telescope.

Perhaps a much more advanced orbiting telescope will be watching someday when Betelgeuse goes supernova, an event which will certainly make it the brightest star in Earth's skies—if only for a few months.

If you'd like to follow along with NASA's New Horizons Mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, please download our FREE Pluto Safari app. It is available for iOS and Android mobile devices. Simulate the July 14, 2015 flyby of Pluto, get regular mission news updates, and learn the history of Pluto.

Simulation Curriculum is the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night, SkySafari and Pluto Safari. Follow the mission to Pluto with us on Twitter @SkySafariAstro, Facebook and Instagram.

First Night Out Series: Measuring Brightness In The Sky

In 120 B.C. Hipparchus, a Greek astronomer, ranked the brightness of stars in the sky on a scale of one to six. He classified the brightest stars he could see as first magnitude and ranked the rest down to the faintest at sixth magnitude.

Astronomers still use this scale to measure the brightness of celestial objects, although it has since been modernized.

The Magnitude Scale

The magnitude scale is logarithmic, so a difference of one point in magnitude is equal to a difference in brightness of about 2.5 times.

The magnitude of stars in the Big Dipper and Little Dipper asterisms. Credit: Starry Night software.

A magnitude-one star is about 2.5 time brighter than a magnitude-two star, and a hundred times brighter than a magnitude-five star.

The lower the magnitude, the brighter the object.

The brighter planets and stars have negative magnitudes. The sun, the brightest object in the sky, has a magnitude of -26, followed by a full moon at magnitude -12.6.

Objects with a magnitude of six or less can be seen without optical aid under ideal observing conditions away from all artificial light.

Where Do Objects Fit in the Scale?

The table below is a list of well-known celestial objects and roughly where they fall on the magnitude scale—some objects, such as Venus, vary in brightness. The magnitude values have been rounded.

| Object | Mag |

| Sun | -26 |

| Full Moon | -12.6 |

| Crescent Moon | -6 |

| Venus (the brightest planet) | -4 |

| Jupiter | -2 |

| Sirius (the brightest star in the sky) | -1 |

| Vega (the brightest star in the Summer Triangle) | 0 |

| Saturn | +1 |

| Polaris (the North Star) and the Stars of the Big Dipper | +2 |

| The Andromeda Galaxy | +4 |

| Uranus and the Faintest Stars Visible with the Naked Eye | +6 |

| Objects You Need Binoculars to See | +7 and greater |

A Few Handy Terms

Here are a few handy terms to keep in mind when reading about the appearance of celestial objects.

Luminosity

Luminosity is the intrinsic brightness of a star—compared to the sun—as it would appear if you were there in orbit around it, rather than viewing it from Earth. The sun's luminosity is 1. Sirius has a luminosity of 23 and Betelgeuse has a luminosity of 55,000.

Brightness

Brightness is the light given off by a celestial object as seen from Earth. Brightness depends on luminosity and the distance from the object.

Magnitude

Magnitude is a logarithmic brightness scale. Magnitude-one objects are 2.512 times brighter than magnitude-two objects, which are 2.512 times brighter than magnitude-three objects, and so on. The difference between magnitude one and magnitude five is one hundred times. The higher the magnitude, the fainter the object. The lower the magnitude, the brighter the object. The brightest stars have negative magnitudes.

If you'd like to follow along with NASA's New Horizons Mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, please download our FREE Pluto Safari app. It is available for iOS and Android mobile devices. Simulate the July 14, 2015 flyby of Pluto, get regular mission news updates, and learn the history of Pluto.

Simulation Curriculum is the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night, SkySafari and Pluto Safari. Follow the mission to Pluto with us on Twitter @SkySafariAstro, Facebook and Instagram.

First Night Out Series: Measuring Distances In The Sky

Measuring the distance from one star to another in the sky is easy when you master using your hands to measure the degrees between objects.

Hold your hand at arm's length:

- The width of your little finger is about one degree—enough to cover the moon and sun, both of which are each half a degree across.

- The width of the first three fingers side-by-side spans about five degrees.

- A closed fist is about ten degrees.

- If you spread out your fingers, the distance from the tip of your first finger to the tip of your little finger is 15 degrees.

- If you spread out your fingers, the distance from little finger to thumb covers about 25 degrees of sky.

Measuring degrees with your hands.

With a bit of practice, this hand system is endlessly useful when measuring your way around the sky.

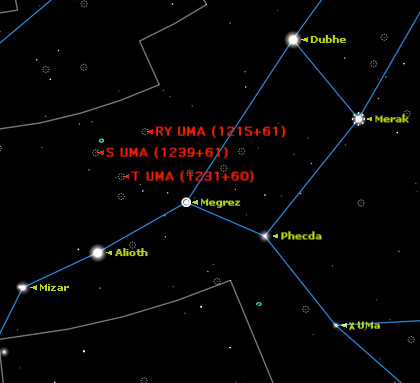

Calibrating with the Big Dipper

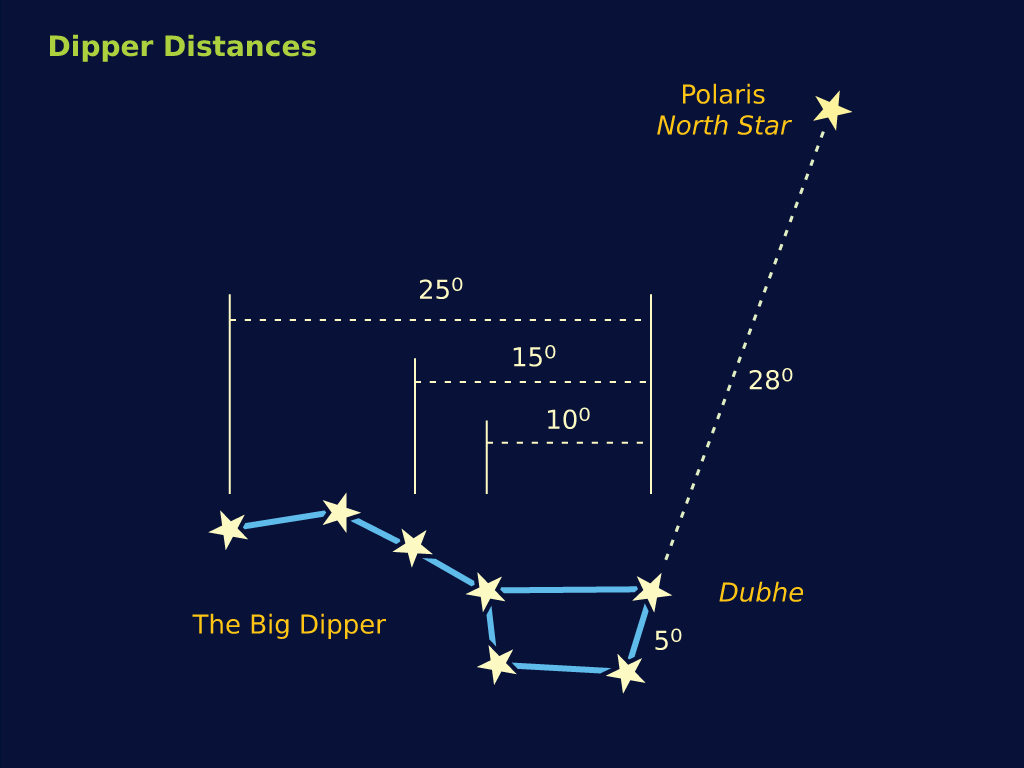

Everyone's hands are slightly different, so you might want to practice and calibrate your own hand measurements using the Big Dipper.

Big Dipper Distances.

Here are the rough distances from Dubhe to several other prominent Big Dipper stars:

| Dubhe to Merak | 5 degrees |

| Dubhe to Megrez | 10 degrees |

| Dubhe to Alioth | 15 degrees |

| Dubhe to Mizar | 20 degrees |

| Dubhe to Alkaid | 25 degrees |

If you'd like to follow along with NASA's New Horizons Mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, please download our FREE Pluto Safari app. It is available for iOS and Android mobile devices. Simulate the July 14, 2015 flyby of Pluto, get regular mission news updates, and learn the history of Pluto.

Simulation Curriculum is the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night, SkySafari and Pluto Safari. Follow the mission to Pluto with us on Twitter @SkySafariAstro, Facebook and Instagram.

Observing Saturn

On Friday, May 22, at 10 p.m. EDT, Saturn will be in opposition to the sun. This means that it will be directly opposite the sun in our sky. It will rise as the sun sets in the evening, shine brightly all night long, and set as the sun rises at dawn.

On May 22, Saturn reaches opposition with the Sun. It will be right on the border between Libra and Scorpius, just above the three stars which form the Scorpion’s claws. Credit: Starry Night software.

If you just look at the sky on a single night, everything seems quite static. But if you watch Saturn over a period of a few weeks and note its position against the background stars, you will see that it is in constant motion.

Currently Saturn is moving with what is called “retrograde motion,” from left to right against the background stars. This is actually an optical illusion caused by the Earth’s much more rapid movement around the sun. Once the Earth is well past Saturn in early August, Saturn will appear to reverse directions and begin moving in its true direction, from right to left.

This retrograde motion puzzled early skywatchers, who though the planets must go around it tiny circles called epicycles. This was because they incorrectly believed that the Earth was fixed in space and everything revolved around it, the “geocentric theory.” Once Copernicus made clear that the sun, not the Earth, was the center of the Solar System, the geometry of the planets’ motion became much simpler.

Saturn, like all the planets, is much smaller in angular size than most people realize. I once tried an experiment to see how much magnification was needed to see Saturn’s rings. With a binocular magnifying 10 times, Saturn looked just like a bright star. With a 15x binocular, I could just see a hint that Saturn was oval rather than round. It took a telescope magnifying 25 times to see Saturn’s true shape, though even then no detail was visible. I generally use magnifications of 150 to 250 times to see the details of Saturn and its ring system.

Saturn really has multiple rings, of which the brightest are the outer A ring and the inner B ring. The A ring is noticeably darker than the B ring, and the two are separated by the dark Cassini Division, named after 17th century Italian astronomer Giovanni Domenico Cassini, who was the first to observe it in 1675. Cassini also discovered four of Saturn’s five brightest moons.

The Cassini Division separates the A and B rings.

Titan, the largest and brightest of Saturn’s moons was discovered in 1655 by Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens. It is visible in even the smallest telescopes. It is the second largest moon in the Solar System (after Jupiter's moon Ganymede), the only moon to have a dense atmosphere, and the only moon other than our own to have been landed on by a spacecraft.

Huygens was also the first person to deduce that Saturn’s rings were flat circular objects in the plane of Saturn’s equator. Further study has shown that they are made up of thousands of tiny fragments of rock and ice. I once watched a star pass behind these rings, and the star continued to be visible, since there is more empty space that rock and ice in the rings, making them translucent.

Saturn’s smaller moons are worth looking for if you have a good telescope. The brighter ones are visible in a 90mm telescope. Because they are in constant motion around Saturn, you need a planetarium program like Starry Night to identify which ones are visible on a given night. Most of the bright moons move in the same plane as the rings, so appear to trace ovals around the planet.

In a telescope at about 150 power, Saturn is small but beautiful in its perfection, the jewel of the Solar System. Look around the planet for its brightest moons. Credit: Starry Night software.

Iapetus is a particularly interesting moon. Its orbit lies outside those of the other bright moons, and is tilted at an angle of 15 degrees compared to the other moons and the rings. Like all major moons in the Solar System, Iapetus always keeps one face permanently turned towards its planet. The side of Iapetus which leads it around in its orbit has encountered a large amount of debris, painting that face of the moon dark black. When that blackened side of Iapetus is facing Earth, at the moon’s greatest elongation east, it is almost two magnitudes fainter than when the trailing side of Iapetus is facing us, at greatest western elongation.

Right now Iapetus is close to its western elongation, so is at its brightest, magnitude 10.1. By greatest elongation east on June 27, it will be at its faintest, magnitude 11.9.

The globe of Saturn itself is rather bland when compared to its more active neighbor Jupiter. It shows a system of darker belts and brighter zones, but their contrast is muted compared to Jupiter. From time to time bright spots have been observed in Saturn’s cloud tops, but they have short lives compared to cloud features on Jupiter. In large telescopes, the polar regions of Saturn take on an olive green color.

It is interesting to observe the pattern of shadows on Saturn. The rings cast shadows on the globe of the planet, and the planet in turn casts its shadow on the rings. I have observed these shadows in a telescope as small as 90mm aperture under steady seeing conditions.

Whenever I observe Saturn in a telescope, I always take a few minutes to just sit back and admire its sheer beauty. Saturn was one of the first objects I looked at when I got my first telescope as a teenager, and I still recall the wonder I felt at witnessing this beauty for the first time with my own eyes: “It really has rings!”

If you'd like to follow along with NASA's New Horizons Mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, please download our FREE Pluto Safari app. It is available for iOS and Android mobile devices. Simulate the July 14, 2015 flyby of Pluto, get regular mission news updates, and learn the history of Pluto.

Simulation Curriculum is the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night, SkySafari and Pluto Safari. Follow the mission to Pluto with us on Twitter @SkySafariAstro, Facebook and Instagram.

First Night Out Series: Finding Your Way Around The Sky

The Big Dipper is a great starting point for learning the night sky. Being circumpolar, it never completely sets or dips below the horizon—it's visible in the night sky year-round!

The Big Dipper itself is not a constellation, but it resides in one called Ursa Major, the Great Bear, the third largest of the 88 constellations. The name originates from the dipper-shaped pattern formed by the seven main stars in the constellation.

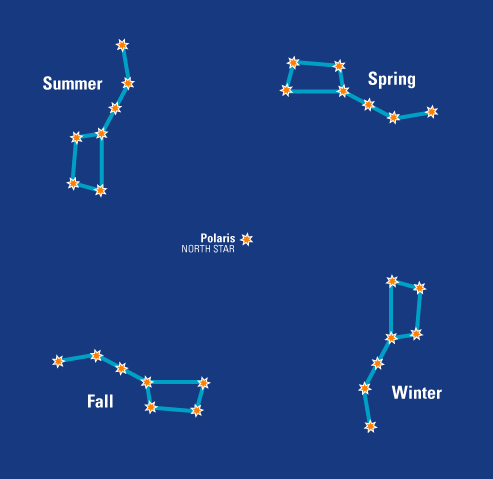

To locate the Big Dipper, face north and look for the seven bright stars that dominate the sky in this direction—they should be easy to find. Depending on the time of year, the pattern formed by these stars appears in a difference orientation, but the shape is always the same:

- In autumn, the dipper appears to be sitting flat.

- In spring, the dipper is upside-down, spilling its contents.

- In summer, it sits upright on its bowl.

- In winter, it sits up on its handle.

The Big Dipper through the seasons.

The stars of the Big Dipper are a handy guide to other stars, constellations, and other thought-provoking objects that may be too faint to spot with the naked eye. Using well-known spots in the sky to find fainter ones is known as star hopping—think of it as an astronomical treasure hunt! And one of the easiest and coolest place to start is with the two end stars that form the front of the dipper's bowl—they point straight to Polaris, the North Star.

All the other stars in the sky seem to turn counterclockwise around Polaris. Polaris itself marks the end of the handle of another pattern, the Little Dipper in Ursa Minor, the Little Bear. If you find Polaris, you know which way is north.

Following the arc of the handle of the Big Dipper points to two of spring's brightest stars—Arcturus and Spica. With a bit of practice, it's surprisingly easy to imagine lines and arcs from star to star and hop from constellations you know to those you're still learning.

The Big Dipper points the way.

The trick to successfully learning the night sky is to use easily recognizable star patterns to find the more difficult ones—just like we used the Big Dipper's stars to find Polaris.

Don't try to learn the entire sky on your first night out. Begin by learning the major constellations and then search out the more obscure patterns as the need and challenge arise.

Like riding a bicycle, once you know a constellation, it's hard to forget it.

If you'd like to follow along with NASA's New Horizons Mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, please download our FREE Pluto Safari app. It is available for iOS and Android mobile devices. Simulate the July 14, 2015 flyby of Pluto, get regular mission news updates, and learn the history of Pluto.

Simulation Curriculum is the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night, SkySafari and Pluto Safari. Follow the mission to Pluto with us on Twitter @SkySafariAstro, Facebook and Instagram.

Double Stars around Boötes

On a May evening many years ago, I made my first exploration of the night sky. The only star pattern I could recognize was the Big Dipper, but with a star chart in a book, I used that to discover the bright star Arcturus in the constellation Boötes.

The curve of the Big Dipper's handle leads to Arcturus, the brightest star in the kite-shaped constellation of Boötes. Surrounding Boötes is an amazing variety of double stars. Credit: Starry Night software.

The trick to learning the constellations is to begin with the stars you know, and use them to identify their neighbors. This same technique, known as "starhopping" is the key to discovering all the wonders hidden amongst the stars.

Start, as I did, with the Big Dipper, high overhead as the sky gets dark at this time of year. The stars that form the Dipper’s handle fall in a gentle arc, and if you project that arc away from the Dipper’s bowl, you come to a bright star. This is Arcturus, the third brightest star in the night sky, and the brightest star in the northern sky. Only Sirius and Canopus, far to the south, are brighter.

Arcturus is bright in our sky for two reasons, first because it is relatively close to us, 38 light years away, and secondly because it is inherently a bright star, much brighter than our Sun. Though larger and brighter, it is a slightly cooler star than our Sun, so appears orange to our eyes.

Although Boötes is supposed to be a ploughman in mythology, its pattern of stars most resembles a kite, with Arcturus marking the bottom of the kite where the tail attaches. Notice the little dots over the second “o†in Boötes: this indicates that the two "o"s are supposed to be pronounced separately, as "bow-oo’-tees," not "boo’-tees."

Once you have identified Boötes, you can use its stars to identify a number of constellations surrounding it. Between it and the Big Dipper are two small constellations, Canes Venatici (the hunting dogs) and Coma Berenices (Bernice's hair). To Boötes left (towards the eastern horizon) is the distinctive keystone of Hercules. Between Hercules and Boötes is Corona Borealis (the northern crown) with Serpens Caput, the head of the serpent, poking up from the south.

Although most stars appear to our unaided eyes as single points of light, anyone with access to binoculars or a telescope soon discovers that nearly half the stars in the sky are either double or multiple stars. Some of these are just accidents of perspective, one star happening to appear in the same line of sight as another, but many are true binary stars: two stars in orbit around each other, similar to the stars which shine on the fictional planet Tatooine in Star Wars.

Every star labeled on this map of Hercules, Boötes, and Ursa Major is a double star, worth exploring with a small telescope. Some, like Mizar in the Dipper’s handle, can be split with the naked eye. A closer look with a telescope shows that this is really a triple star. Others require binoculars or a small telescope. Some of the finest are Cor Caroli in Canes Venatici, Izar (Epsilon) in Boötes, Delta Serpentis, and Rho Herculis.

One of the joys of double star observing is the colour contrasts in some pairs. Others are striking for matching colours and brightness. My favorites are stars of very unequal brightness, which look almost like stars with accompanying planets.

Also marked on this chart are three of the finest deep sky objects: the globular clusters Messier 13 in Hercules and Messier 3 in Canes Venatici, and the Whirlpool Galaxy, Messier 51, tucked just under the end of the Big Dipper’s handle. You will probably need to travel to a dark sky site to spot this galaxy. A six-inch or larger telescope will begin to reveal its spiral arms, including the one that stretches out to its satellite galaxy, NGC 5195.

If you'd like to follow along with NASA's New Horizons Mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, please download our FREE Pluto Safari app. It is available for iOS and Android mobile devices. Simulate the July 14, 2015 flyby of Pluto, get regular mission news updates, and learn the history of Pluto.

Simulation Curriculum is the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night, SkySafari and Pluto Safari. Follow the mission to Pluto with us on Twitter @SkySafariAstro, Facebook and Instagram.

The Next Pluto Mission: Part II

ROCKET SCIENCE 101

All spacecraft are limited by Tsiolkovsky’s rocket equation, named after Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, the 19th century Russian founding father of astronautics. Tsiolkovsky’s rocket equation determines the speed a rocket can attain, based on the rocket’s exhaust velocity, the “dry mass” of the rocket (without fuel), and the amount of fuel it carries. Here’s the essential take-away: for your rocket to go faster than the exhaust from its burning fuel, it needs to carry a lot more fuel. You need exponentially more fuel the faster you want it to go. And this is also true in reverse: if you are already going very fast, your rocket will need exponentially more fuel to slow down.

Here’s the math:

DV = Ve * ln ( (Md + Mp) / Md )

DV = Delta-V, total velocity change produced by rocket after all fuel is exhausted

Ve = Exhaust velocity

Md = Dry mass of rocket

Mp = Mass of propellant (fuel) carried by rocket

New Horizons has a dry mass of 400 kilograms, and carries about 78 kilograms of hydrazine fuel. That fuel has an exhaust velocity of about 2.2 km/sec. Plugging those numbers in, that means New Horizons’ rocket motors can change its speed by at most 390 meters per second. New Horizons is moving past Pluto at 14 kilometers per second. So this is not nearly enough to slow down and achieve orbit around Pluto. To shed 14 km/sec, New Horizons would need to burn 580 times its own weight - or 232 metric tons - of hydrazine fuel.

A more efficient fuel, like the liquid hydrogen and oxygen in the Centaur upper stage, has an exhaust velocity around 4.4 km/sec. That improves things quite a bit, but New Horizons would still have to carry 24 times its dry weight in fuel to slow down from 14 km/sec. For comparison, the Centaur upper stage which boosted New Horizons toward Pluto has a dry mass of 2.2 tons, and carried 20.8 tons of fuel. Its maximum theoretical delta-V is 10.2 km/sec. In other words, the fully fueled Centaur booster, carrying no space probe at all, could not slow itself down enough to enter Pluto orbit. Some even larger rocket would have to be built to slow the Pluto orbiter into orbit around Pluto.

And don’t forget - that Pluto orbiter and its 50+ tons of fuel would still have to be launched from Earth, on an escape trajectory toward Pluto, in the first place. The Atlas V that launched New Horizons couldn’t possibly do this. The largest rocket under construction - NASA’s Space Launch System - can deliver a maximum payload of 7 tons to Jupiter. That is hopelessly insufficient to deliver a Pluto probe with 50 tons of fuel to Pluto.

GOING SMALL

Instead of making a larger rocket, how about making a smaller payload? During the early 2000s, while New Horizon was in its early design phases, a (literally) small revolution was taking place in satellite design. The first CubeSats packed all the essential elements of an functioning satellite into a 10x10x10 cm cube weighing less than 1 kilogram, and were launched in 2003. To date, hundreds of CubeSats have been launched, and are becoming increasingly capable as technology advances. On the first SLS launch, scheduled for late 2018, NASA plans to deploy three CubeSats from the SLS upper stage as it passes the Moon, to see how well they’ll perform at interplanetary exploration tasks. (By the way: want to win $5 million? You can compete for the chance to launch your own lunar CubeSat on the maiden SLS launch. Here’s how: http://www.nasa.gov/cubequest/details

CubeSats in space.

In 2014, a San Francisco startup called Planet Labs launched a constellation of several dozen CubeSats. These CubeSats are capable of imaging the entire Earth’s surface at a resolution of 5 meters, every day. Each of those “3U” CubeSats weighs about 4 kilograms. Suppose the next Pluto mission wasn’t a single orbiter, but rather 10 tiny 3U CubeSat Pluto orbiters. This whole fleet of Pluto orbiters would weigh 40 kilograms - about 1/10th the mass of New Horizons, and the same as a 6th grader. A single ton of liquid hydrogen/oxygen fuel could decelerate this tiny payload into Pluto orbit. Launch from Earth on an SLS, with Jupiter flyby and gravity assist, then direct orbit insertion around Pluto, becomes thinkable.

With this approach, there are a lot of benefits - you get ten Pluto orbiters instead of one - but there are a lot of challenges to overcome. Solar panels are useless at 40 times the Earth’s distance from the Sun. So our hypothetical Pluto CubeSat orbiters would need require tiny nuclear reactors for electricity. A large radio dish several meters across would be needed to beam any useful amount of data back home. Deploying such a dish from a spacecraft 10 centimeters across is not easy, although inflatables are currently in development. Interplanetary laser communication systems, as demonstrated in 2013 by NASA’s LADEE moon orbiter, may be the right answer. These are the cutting edges of today’s spacecraft technology, and you can see why NASA is funding competitions to spur their development.

A NEW DAWN

On September 28th, 2007, eighteen months after New Horizons launched, another NASA dwarf planet explorer lifted off. Less than four years later, in July 2011, the Dawn mission entered orbit around the asteroid Vesta. It departed Vesta in September 2012, and entered orbit around the dwarf planet Ceres just this past March.

Dawn spacecraft at Ceres.

Dawn is NASA’s first interplanetary mission to be propelled by electricity. Instead of a high-thrust rocket engine burning many tons of chemical fuel over the course of a few minutes, Dawn’s electric engines emit tiny amounts of electrically charged ions - at much higher velocities than chemical rocket exhaust. Dawn’s engines only consume three milligrams of fuel per second. But the ions emitted from Dawn’s engines have an exhaust velocity over 31 kilometers per second. That produces a thrust of 91 millinewtons, or about the force a piece of paper exerts on your hand when you pick it up. Still, the thrust is constant, adding 24 km/hour per day, day after day, to the spacecraft’s velocity. Over the course of 67 days, the accelerations adds up to a velocity of 1,000 mph. Dawn carried 425 kilograms of propellant (as opposed to the Centaur booster’s 20.8 tons), and yet Dawn can perform a velocity change of more than 10 km/sec over the course of its mission.

What if New Horizons were equipped with an ion engine, like Dawn’s? Some modifications would be needed. Again, solar panels are near-useless at Pluto’s distance from the Sun, so “New Dawn” would need a nuclear reactor quite a bit more powerful than New Horizon’s (whose nuclear reactor produces 250W of electrical power vs. Dawn’s 1400W solar panel array.) Dawn also weighs about twice as much as Hew Horizons (780 vs 400 kg dry.) It seems reasonable to guess that a nuclear-powered, ion-propelled Pluto orbiter with the same 30 km/sec exhaust velocity as Dawn could be built with a total spacecraft dry mass of one metric ton. Plugging those numbers into Tsiolkovsky’s rocket equation, our “New Dawn” Pluto orbiter would need 620 kilograms of Xenon fuel to decelerate from 14 km/sec cruise velocity into orbit around Pluto. Something like this could conceivably be launched from Earth by the same Atlas V 551 that actually launched New Horizons. It could certainly be launched by the Falcon Heavy or SLS.

How long might this spacecraft take to reach Pluto? Again, we’ll assume a gravity-assist slingshot by Jupiter, barreling toward Pluto at ~14 kilometers per second. “New Dawn”, firing its ion engine continuously, would need 1.7 years to shed this velocity as it approached Pluto. Given an 8-year cruise from Jupiter to Pluto, this seems amply doable.

Dawn was launched little more than a year after New Horizons. Its technological development schedule paralleled New Horizons’. The next time Jupiter and Pluto properly align for a gravitational slingshot maneuver will be in 2018-2019. Using today’s ion propulsion technology, NASA could conceivably mount a New Dawn-like Pluto orbiter mission in just a few years.

If you'd like to follow along with NASA's New Horizons Mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, please download our FREE Pluto Safari app. It is available for iOS and Android mobile devices. Simulate the July 14, 2015 flyby of Pluto, get regular mission news updates, and learn the history of Pluto.

Simulation Curriculum is the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night, SkySafari and Pluto Safari. Follow the mission to Pluto with us on Twitter @SkySafariAstro, Facebook and Instagram.

The Next Pluto Mission: Part I

On July 14th, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft will fly by Pluto. It’s among NASA’s most impressive achievements to date. But what might come next?

New Horizons was launched on January 19, 2006, atop an Atlas V 551 rocket with a Centaur upper stage. That upper stage, and the New Horizons probe inside, had highest launch speed of any man-made object leaving Earth. New Horizons crossed the Moon’s orbit just 9 hours after launch - the Apollo astronauts took three days - and reached Jupiter in just over a year (the Voyager spacecraft took nearly three years).

Launch of New Horizons. The Atlas V rocket on the launchpad (left) and lift off from Cape Canaveral. New Horizons ' launch was the fastest ever to date, at 16.26 km/s.

New Horizons then used Jupiter’s gravity to slingshot itself onto a hyperbolic trajectory that intersects Pluto just over eight years later.

A composite image of Jupiter and Io, taken on on February 28 and March 1, 2007 respectively. Jupiter is shown in infrared, while Io is shown in true-color.

By the time New Horizons reaches Pluto this July, it will be moving at nearly 14 kilometers per second relative to the planet. That’s 30% faster than the ISS orbits the Earth. The probe will flash by Pluto in just a few hours. New Horizons can’t slow down. It doesn’t carry enough fuel to enter orbit around, or land on, Pluto. Nor was it designed to. Instead, New Horizons will keep flying past Pluto, into a vast outer region of our solar system called the Kuiper Belt. New Horizons may fly by a few Kuiper Belt Objects after its Pluto encounter, a few candidate KBOs are being selected now.

But what if New Horizons had been intended to stay longer at Pluto? After a flyby, the next step in planetary exploration is an orbiter to perform extended surface observations, and then a lander. Are these things even possible, within current technology? Pluto is forty times farther from the Earth, than Earth is from the Sun. Transmissions radioed back by New Horizons take four and a half hours to reach us. Is there any hope of catching anything more than a fleeting glimpse of such a distant place?

If you'd like to follow along with NASA's New Horizons Mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, please download our FREE Pluto Safari app. It is available for iOS and Android mobile devices. Simulate the July 14, 2015 flyby of Pluto, get regular mission news updates, and learn the history of Pluto.

Simulation Curriculum is the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night, SkySafari and Pluto Safari. Follow the mission to Pluto with us on Twitter @SkySafariAstro, Facebook and Instagram.

Asterisms and Constellations

On a recent warm and humid summer night, sky transparency was very poor. Only the brighter stars punched through the water-laden atmosphere but three stars were very prominent. They formed a triangular pattern aptly called the Summer Triangle.

The Summer Triangle begins to rise in the Spring. As seen from mid-northern latitudes in mid-May near midnight.

The Summer Triangle is an example of an asterism: a group of stars that form a recognizable pattern or shape. The Big Dipper, the Little Dipper and the Great Square of Pegasus are other examples of asterisms.

Asterisms are often confused with constellations and indeed, in ancient times, constellations were mythological figures, animals or objects that were seen in groupings of stars.

The Big Dipper asterism as seen from mid-northern latitudes in mid-May at 10:00 p.m.

Almost everyone in North America is familiar with the Big Dipper which is part of the figure of the Big Bear, or the constellation of Ursa Major.

The Big Dipper asterism belongs to the constellation Ursa Major (Great Bear).

The modern constellation of Ursa Major includes all stars within an area defined by the International Astronomical Union in 1930. So the star 24 Ursae Majoris "belongs" to the constellation Ursa Major even though it is not part of the figure of the bear.

Modern constellation boundaries

Some asterisms such as the Big Dipper, the Sickle of Leo, the teapot of Sagittarius and the Great Square of Pegasus have been known for a long time. All are best appreciated when viewed without optical aid because of their large angular size.

But over the years, people using binoculars and telescopes have come across other striking asterisms and some of these have become well known to amateur astronomers.

Here are some examples.

The Diamond Ring

A tight group of 7th and 8th magnitude stars with Polaris as the "solitaire". Best seen with binoculars in a dark sky or a small telescope with a low power eyepiece showing about a 1° field.

The Coathanger

RA = 19h 25m, Dec = 20° 04'

A group of fifth and sixth magnitude stars in Vulpecula appearing like an upside down coathanger to northern hemisphere observers. Use binoculars for best views.

ET Cluster

RA = 1h 19 m, Dec = 58° 17.5'

This open cluster, also known as NGC 457, is located in Cassiopeia. With a bit of imagination you can make out the figure of ET. (Hint: the two bright stars are ET's eyes). Because of its small size, a telescope is needed to make out this asterism.

If you'd like to follow along with NASA's New Horizons Mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, please download our FREE Pluto Safari app. It is available for iOS and Android mobile devices. Simulate the July 14, 2015 flyby of Pluto, get regular mission news updates, and learn the history of Pluto.

Simulation Curriculum is the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night, SkySafari and Pluto Safari. Follow the mission to Pluto with us on Twitter @SkySafariAstro, Facebook and Instagram.

Virgo and Her Treasures

Although Virgo is the second largest constellation in the sky (after Hydra), it is poorly known to casual skywatchers. That’s because it contains only one first magnitude star, Spica, and its other stars do not form an easily recognizable pattern like the Big Dipper or Orion.

Virgo is the second largest constellation by area, and is well placed just after dark for exploration. Credit: Starry Night software.

Most of the stars which form the pattern of Virgo are third or fourth magnitude, so are hard to see unless you have dark country skies. City dwellers will need binoculars to see them. Starting from bright Spica there is a chain of four stars to its right, with Porrima (Gamma Virginis) in the middle the brightest. Two stars extend northwards from Porrima, ending with Vindemiatrix.

Porrima is one of the finest double stars in the sky, but has been hard to split in recent years because the apparent distance between its two components had been closing. It is once again opening up, and its separation of slightly more than 2 arc seconds makes it easy to split in all but the smallest telescopes.

There are two other double stars in neighboring constellations worth a look: Algorab in Corvus and Zubenelgenubi in Libra, which can be split in binoculars.

If Virgo has few bright stars it makes up for it by containing more galaxies than any other constellation in the sky. It is most famous for containing the Virgo Galaxy Cluster, the nearest galaxy cluster to our own Local Group. Located 60 million light years distant, this is the richest cluster of galaxies in the sky.

The Virgo Galaxy Cluster is an easy starhop from Vindemiatrix. Credit: Starry Night software.

You can locate the Virgo Cluster by sweeping first westward from Spica to Porrima, and then northward to Vindemiatrix. Five degrees west of Vindemiatrix is Rho Virginis at the center of a distinctive Y-shaped group of stars. The Y points upwards to the galaxy cluster. The problem with the Virgo Cluster is not spotting the galaxies, but trying identify which is which. This chart <> will help you to follow the starhop and identify the galaxies. The secret to observing galaxies is to view them from a location with dark skies on a moonless night.

Charles Messier in the Eighteenth Century observed and catalogued eight galaxies in this cluster, plus six more just across the border in Coma Berenices. Two more Messier galaxies are outliers from the main Virgo Group, Messier 49 and Messier 61.

The final Messier galaxy in Virgo is one of the brightest galaxies in the sky and lies slightly nearer than the rest of the Virgo galaxies, 50 million light years distant. This is the famous Sombrero Galaxy, number 104 in Messier’s catalog. It can most easily be found by following a starhop which starts at Gienah, the upper right star in Corvus. In binoculars you can see a long chain of stars extending northeastward from Gienah, ending in a small triangle followed by a group of stars shaped like an arrow. The arrow points right at the Sombrero Galaxy.

This starhop from Gienah in Corvus will lead you directly to the Sombrero Galaxy, Messier 104. Credit: Starry Night software.

If you'd like to follow along with NASA's New Horizons Mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, please download our FREE Pluto Safari app. It is available for iOS and Android mobile devices. Simulate the July 14, 2015 flyby of Pluto, get regular mission news updates, and learn the history of Pluto.

Simulation Curriculum is the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night, SkySafari and Pluto Safari. Follow the mission to Pluto with us on Twitter @SkySafariAstro, Facebook and Instagram.

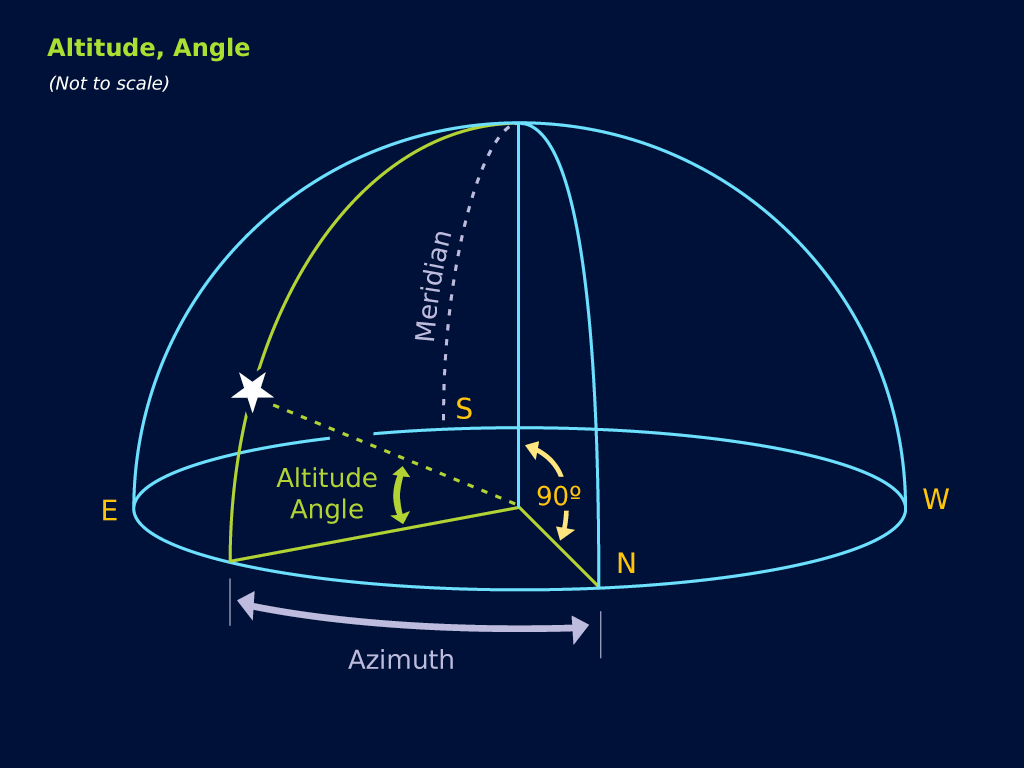

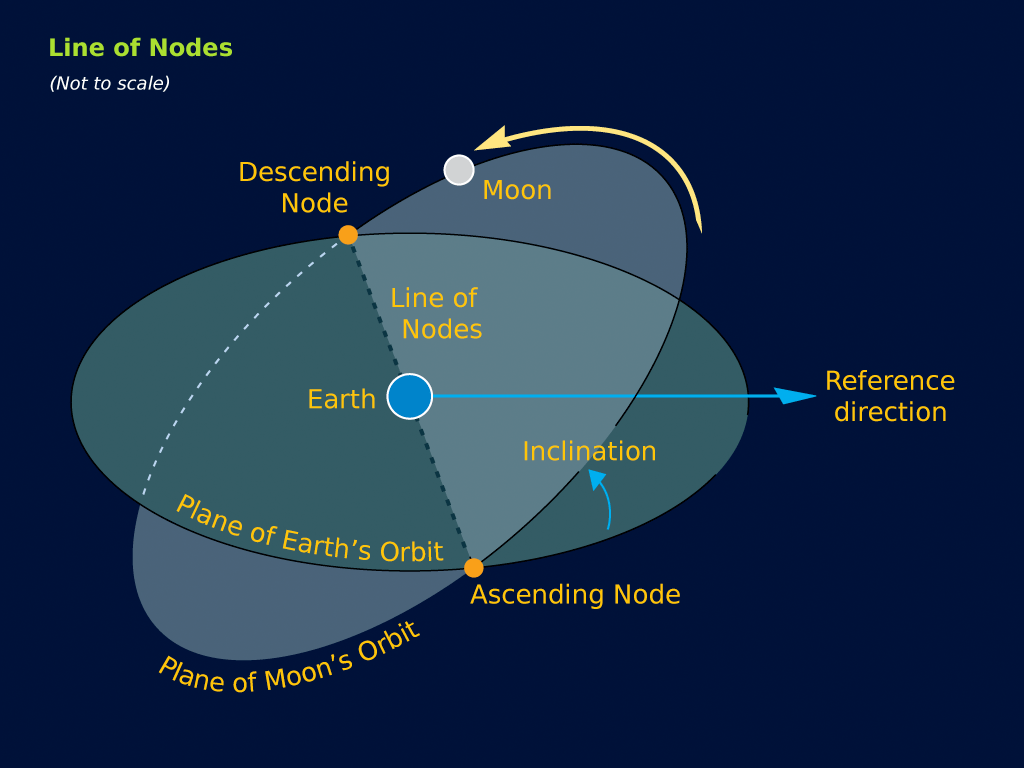

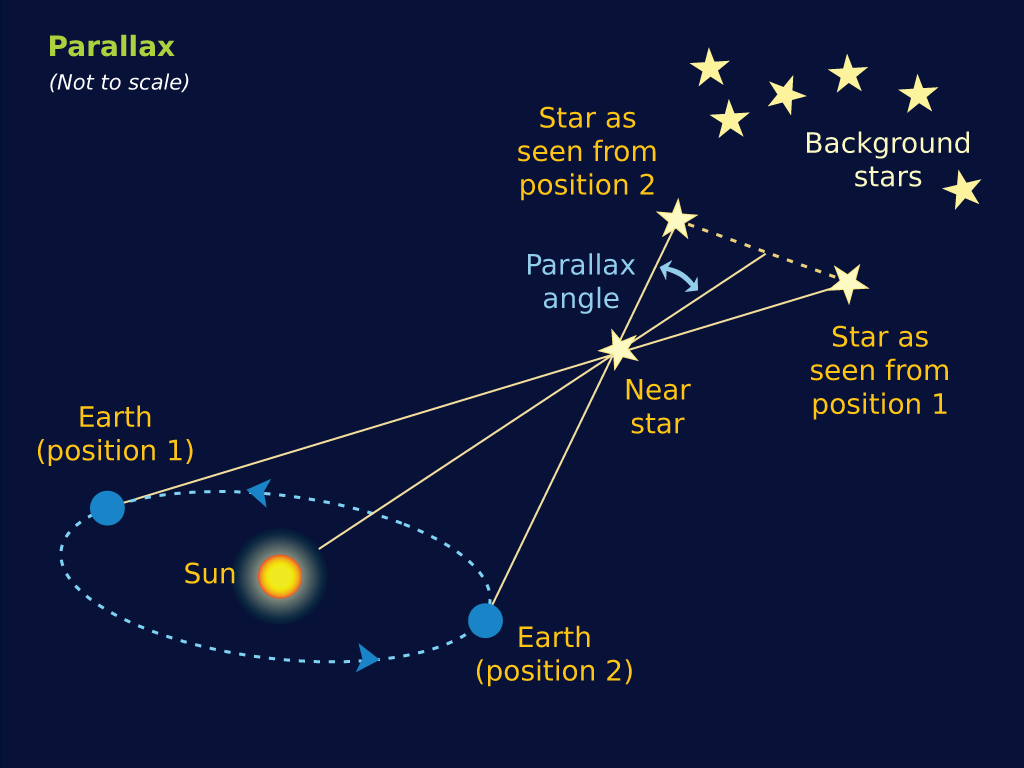

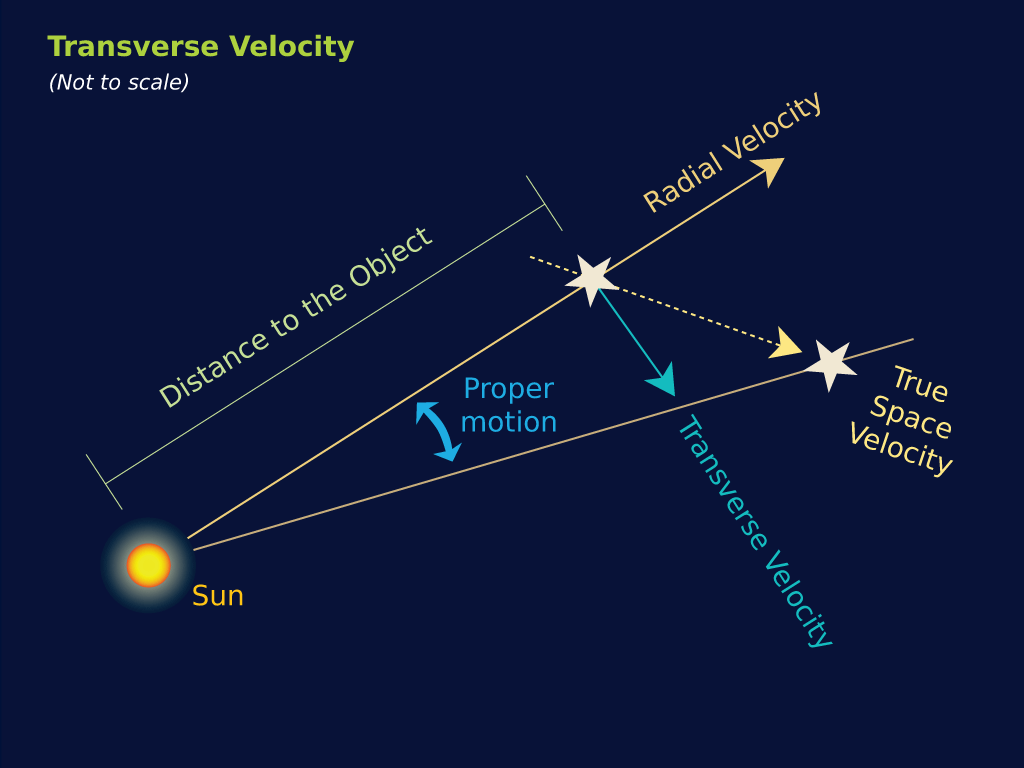

Astronomy Concept Diagrams

Explain difficult astronomical concepts with clear, concise diagrams from Starry Night Education. Click on each image to view a larger version. Feel free to use in your classroom or outreach activities.

If you'd like to follow along with NASA's New Horizons Mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, please download our FREE Pluto Safari app. It is available for iOS and Android mobile devices. Simulate the July 14, 2015 flyby of Pluto, get regular mission news updates, and learn the history of Pluto.

Simulation Curriculum is the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night, SkySafari and Pluto Safari. Follow the mission to Pluto with us on Twitter @SkySafariAstro, Facebook and Instagram.

Astronomer's Spring Fever

“In spring a young astronomer’s fancy lightly turns to thoughts of…”

It’s spring where I live, a very short-lived season in southern Canada; remnants of snow in the woods, yet I've already swatted my first mosquito. The spring sky is also short-lived because of the Sun’s rapid travel northwards at this time of year. It seems as if winter’s brilliant constellations are replaced by the summer ones in a few short weeks.

The constellation Leo as seen from mid-northern latitudes on May 10 at 9:00 p.m.

Leo galaxies as seen from mid-northern latitudes on May 10 at 9:30 p.m.

It’s now warm enough at night to be able to spend a couple of hours in relative comfort with the stars. This is a good time of year to begin new observing projects. If you’re a newcomer to astronomy, you might enjoy the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada’s “Explore the Universe”program. You don’t have to be a member to participate; just download the program brochure and get started. It will introduce you to the wide variety of objects in the night sky, and won’t take you forever to complete. All you need for most of it is your naked eye, a small pair of binoculars, and a reasonably dark sky.

If you’re more advanced in astronomy, you might take on a more challenging project, such as observing all of the 110 objects in Charles Messier’s catalog of deep sky objects. These include the brightest and best objects in the northern sky, and is considered “basic training” for deep sky observers. All the objects are plotted in Starry Night and SkySafari.

Spring is also the time for spring cleaning. It’s a good time to make sure your astronomical equipment is tuned up and ready to perform at its best. Please note that this usually doesn’t involve cleaning your telescope’s main lens or mirror. Unless you follow very careful procedures, you’re more likely to do damage to your optics than to improve the view. A bit of dust won’t do any harm. What is required is an optical tune-up, called collimation, to make sure your telescope’s optics are properly aligned. This is primarily required by Newtonian reflectors and Schmidt-Cassegrains; refractors and Maksutovs are factory aligned and best left alone unless you really know what you’re doing. Collimation is a painless procedure once you’ve done it a few times; your telescope’s operating manual should contain all the information you need. For Newtonians, a simple collimating eyepiece is a handy aid.

Spring is also a time when many amateur astronomers start leafing through the ads and catalogs of the various manufacturers looking for new hardware to enhance their viewing experience. Every telescope is a compromise of some kind, so many astronomers end up owning more than one telescope. If you already own the large Dobsonian reflector which most of us recommend for beginners, you might consider a small “grab-and-go” refractor which will give you wide field views.

I’m always surprised at how many amateur astronomers own a telescope but not a pair of binoculars. I personally find binoculars to be an indispensable part of my observing “kit.” Not only are they a wonderful observing tool in their own right, giving wide rich fields of view without the hassles of mounts and finders, but they are also an essential part of finding objects by starhopping. A pair of binoculars with the same field of view as your telescope’s finder allows you to practice a starhop comfortably before attempting it with finder and telescope. I own several different sizes of binoculars, but find that I use my 10x50s more than any other size: light in weight, easy to hand hold, and very wide field.

If you become really addicted to binocular views, you might want to invest in a pair of giant binoculars. Because of their weight and magnification, these usually need to be mounted on a tripod.

Most scopes come with one or two basic eyepieces, usually 25 mm and 10 mm Plössl types. These are fine to get you started, but they only hint at the versatility of which an astronomical telescope is capable. After you’re comfortable using these basic eyepieces, you may want to increase your range with a low power wide field eyepiece.

At the other end of the scale, you may want to get up close and personal with the Moon and planets with a specialized planetary eyepiece.

You may choose this spring to embark on a totally new area of astronomy. Many astronomers concentrate on the stars visible at night, but forget the star closest to us, the Sun. A solar filter on the front of your telescope will let you watch sunspots as they rotate across the face of the Sun. You may also want to explore the solar flares and prominences visible with a dedicated Hydrogen Alpha telescope like this:

Another area to explore is astrophotography. Most telescopes can easily be coupled with today’s digital cameras to photograph the Sun, Moon, and bright planets. If your scope has a motorized equatorial mount, you can easily make “piggyback” images by mounting your camera on the piggyback bolt included on the tube rings of many mounts.

However you choose to celebrate spring fever, get out there and enjoy these pleasant spring evenings!

If you'd like to follow along with NASA's New Horizons Mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, please download our FREE Pluto Safari app. It is available for iOS and Android mobile devices. Simulate the July 14, 2015 flyby of Pluto, get regular mission news updates, and learn the history of Pluto.