EXPLORING THE EARTH is a regular column that examines various aspects of Earth Science through the lens of The Layered Earth software. This newsletter examines the recent massive earthquake that occurred in Ecuador and how The Layered Earth software can be used to illustrate several unique features relating to this geological event.

Read moreThe December Solstice

On Monday, December 21, the Sun reaches its southernmost declination of the year, resulting in the shortest day and longest night for people in the northern hemisphere. Credit: Starry Night software.

Next Tuesday or Wednesday marks a major turning point in the annual cycle of the seasons. The sun reaches its southernmost position in the sky, resulting in the shortest day of the year in the northern hemisphere, and the longest day of the year in the southern hemisphere.

The solstice gets its name from the apparent stop (“stice”) in the motion of the sun (“sol”). This was carefully recorded by the earliest astronomers; monuments like Stonehenge are thought to have been used to mark the extreme positions of the sun in the sky. The December solstice has long marked the beginning of the new year, and it’s mainly because of slippage in our calendar that it now occurs eleven days before the “official” New Year, January 1.

Solstice day is a day of celebration in many cultures. The Romans knew this as “Saturnalia,” and the early Christians adopted this date to mark the birth of Christ, so that they could celebrate without drawing the attention of their Roman masters.

You’ll notice I said, “Tuesday or Wednesday.” That’s because, although the time of solstice is exactly the same everywhere in the world, because of our local clocks it falls on different days in different places. The exact time of solstice this year is December 22 04:48 coordinated universal time, the time used by astronomers and pilots everywhere.

In England, where the prime meridian lies, the solstice will occur a 4:48 a.m. GMT on Wednesday, December 22. Similarly, it will occur in Europe and Africa in the early hours of Wednesday morning.

In North America, we subtract a number of hours from UTC to get our local times. In most of eastern North America, we are on Eastern Standard Time, and subtract 5 hours, so the solstice falls at 11:48 p.m. on the previous day, Tuesday, December 21. The farther west we go in North America, the earlier the solstice occurs in the evening, so that on the Pacific coast it occurs at 8:48 p.m. PST.

Remember, these are all exactly the same time in the broader scheme of things; local times are just vagaries of the way we handle time around the world.

The graphic shows the sky as it would appear at the time of solstice from a location where the solstice occurs at noon, which this year would be Vietnam. Through the magic of Starry Night software, we have turned the blue sky transparent and have added the two coordinate systems we use to mark positions in the sky.

The red line across the sky marks the celestial equator, half way between the celestial north and south poles. It shows 18h on the meridian because we measure right ascension, the celestial equivalent of longitude, from the vernal equinox, exactly 9 months ago.

The green line marks the ecliptic, the path that the sun appears to follow across the sky. The sun is at its southernmost position, at a declination (celestial equivalent of latitude) of exactly 23 degrees and 26 minutes, which just happens to be the exact angle at which the Earth’s poles are tilted from the ecliptic.

The height of the sun above the horizon on solstice day depends on your latitude on the surface of the Earth. Where I live in southern Canada, it hangs very low in the southern sky, barely 22 degrees above the horizon. For anyone north of the Arctic Circle, it never rises at all. Even in the southernmost continental United States, it’s barely 42 degrees above the horizon, less than half way up the sky.

In the southern hemisphere, the situation is reversed. The December solstice marks the longest day in the year, combined with the shortest night. Longer days mean more hours of sunshine and warmer weather.

You may have noticed that I have avoided using the words “winter” and “summer.” That’s because, even though the sun’s position in the sky is responsible for our seasons, it does not match exactly with the seasons as we experience them. That’s because there is a lag of about six weeks between the astronomical season markers, solstices and equinoxes, and the actual seasons.

The Earth is a complex ecological system, and it takes a while for the sun’s movement to effect the temperature. Sometimes the astronomical markers are referred to as “the first day of…” which makes some sense, if the seasons were exactly 3 months long. However, the lengths of the seasons in any particular location tend to vary depending on local conditions. Hence the old joke about the Canadian seasons: eleven months of winter and one month of bad sledding.

The Super-Blood-Moon Lunar Eclipse

This Sunday evening, 9/27, stargazers will see a rare supermoon lunar eclipse. If you miss it, the next one isn't until 2033! What makes this event so special?

A Full Moon

First, the moon will be full, as it always must be for a lunar eclipse to occur. This is a special full moon, all on its own, because this is the harvest moon. Traditionally, this designation goes to the full moon closest to the autumnal equinox. In two years out of three, the harvest moon appears in September, but every third year it occurs in October.

At this time of year, corn, pumpkins, squash, beans, and wild rice—the chief Native American staples—are ready for gathering; and at the peak of the harvest, farmers could work into the night by the light of this full moon.

Most of the year, the moon rises an average of 50 minutes later each night, but for the few nights around the harvest moon, the moon seems to rise at nearly the same time each night: just 25 to 30 minutes later across the United States, and only 10 to 20 minutes later for much of Canada and Europe.

A Supermoon

Secondly, the full moon will be at its closest to Earth in all of 2015, what is known to astronomers as a perigee moon. In recent years this has become known as a “supermoon.” Perigee (meaning “closest to Earth”) occurs at 10 p.m. EDT, the moon being a mere 222,374 miles (357,877 km) from Earth.

In fact, the human eye can’t detect the 5 percent difference in size between the moon at perigee and the moon at apogee (farthest from Earth), but everyone who looks at the moon Sunday night will swear it looks bigger than usual. Partly that is because, when seen low on the horizon, the human eye and brain combine to create an optical illusion known as the moon illusion, whereby the moon (and other objects) seen close to the horizon seem larger than when seen overhead.

The moon is the same size regardless of how low or high it is above the horizon. To prove this to yourself, cut out a circle just big enough to block the moon at arm's length and use it to see for yourself that its size stays the same as it rises in the sky.

The only noticeable effect of a perigee moon is that the ocean tides will be a bit higher than usual for the day of full moon and the next three days.

A Total Lunar Eclipse

The third, and most important part of this special event, is that we will have a total eclipse of the moon. At most full moons, the sun, Earth and moon line up approximately, but because of the tilt of the moon’s orbit, the moon passes above or below the Earth’s shadow, and avoids being eclipsed.

At certain points in the moon’s orbit, sun, Earth, and moon line up exactly, and the Earth’s shadow falls across the face of the moon, and we have a lunar eclipse. This is what will happen Sunday night.

The moon’s shadow has two parts: a darker inner part called the umbra, and a lighter outer part called the penumbra. This is because the sun is not a point source of light, so its light leaks around the edge of the Earth, and results in an unsharp shadow. In passing through the Earth’s atmosphere, the light turns red or orange, so that the light that actually reaches the moon is tinted by thousands of sunsets and sunrises all around the periphery of the Earth.

One result of these multiple sunrises and sunsets is that the moon during an eclipse is often tinted red, which is the origin of the idea of a lunar eclipse being a “blood moon.” It isn’t a far stretch of the human imagination to turn this “blood moon” into a portent of disaster.

A lot has been made in the media of this eclipse being the fourth event in a foursome of total eclipses known as a “lunar tetrad.” There really is nothing unusual about four lunar eclipses in two years, since we usually average at least two lunar eclipses every year, though not all are total.

In fact, there was no tetrad of total eclipses at all, because the last lunar eclipse, on April 4, was not really a total eclipse. According to the usual way of calculating eclipses, the moon spent only 4 1/2 minutes in the umbral shadow, but recently this calculation method has been corrected, resulting in the April eclipse failing to be total at all.

This Sunday’s lunar eclipse is a true total eclipse, with the moon being in the umbra for a full hour and twenty-two minutes.

When To See It

Observers in eastern and central regions of North America will get to see the whole eclipse; those further west will see the moon rise already partially eclipsed. Observers in Europe and Africa will see the eclipse before dawn on Monday, September 28.

This brings up the question of dates and times, which often causes confusion. Even a usually reliable source like Canada’s Weather Network, got the date of this eclipse wrong.

Officially, mid-eclipse occurs on September 28 at 02:47 Universal Time, which is the same as Greenwich Mean Time (but NOT British Summer Time). Subtracting 4 hours, this places mid-eclipse in the Eastern Daylight Time zone at 10:47 p.m. on the evening of September 27; the date changes at midnight. So be sure you look for the eclipse on Sunday evening. If you wait until Monday evening, you will be a day late.

Here are the important times in Eastern Daylight Time; if you’re using CDT, MDT, or PDT, the times will be earlier by 1, 2, or 3 hours.

EDT

08:11:46 Moon enters penumbra

09:07:12 Moon enters outer edge of umbra

10:11:11 Moon completely in umbra

10:47:09 Mid-eclipse

11:23:07 Moon begins to emerge from umbra

12:27:06 Moon completely out of umbra

01:22:33 Moon leaves penumbra

As always, we look forward to your pictures of this beautiful event.

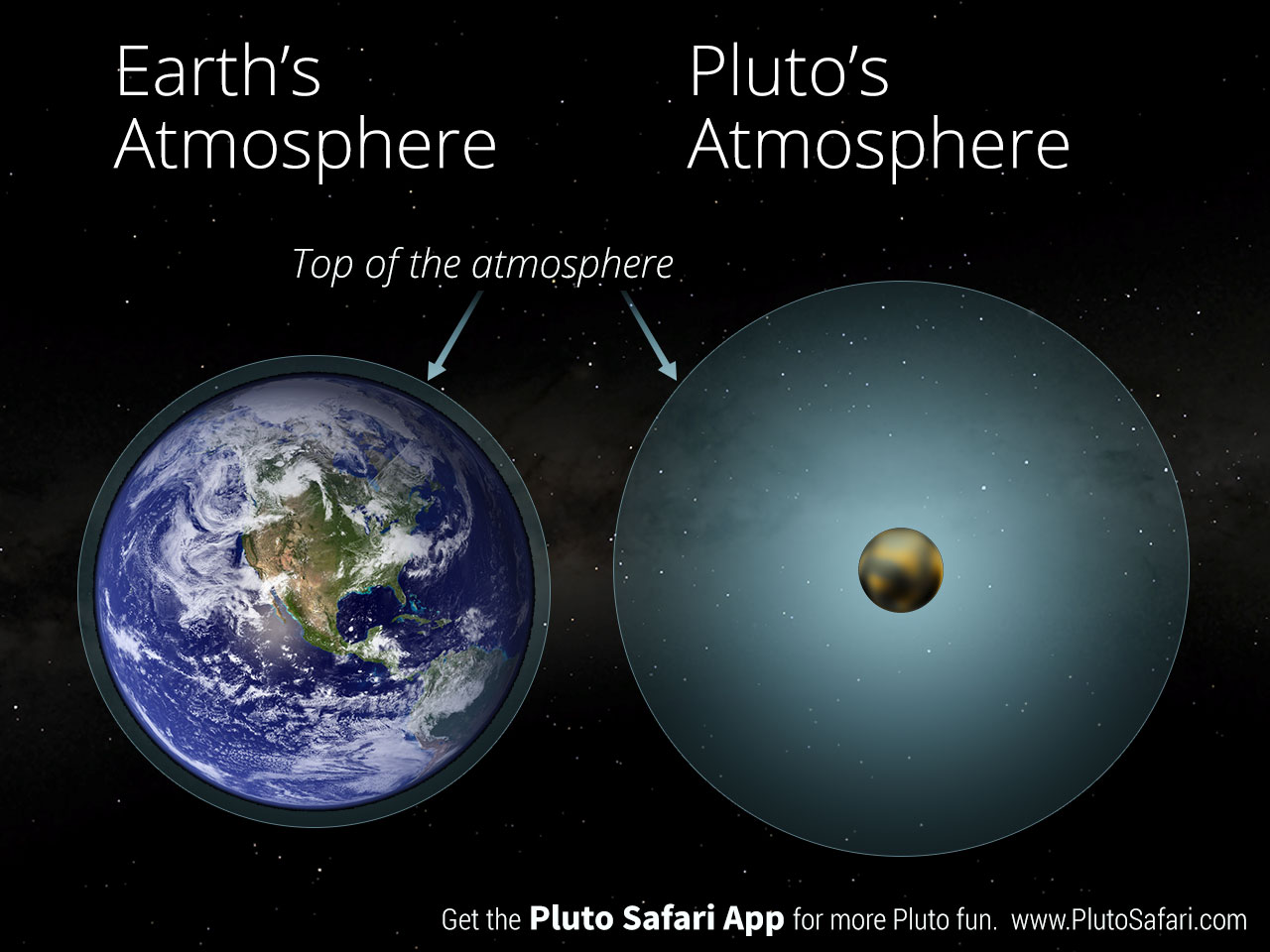

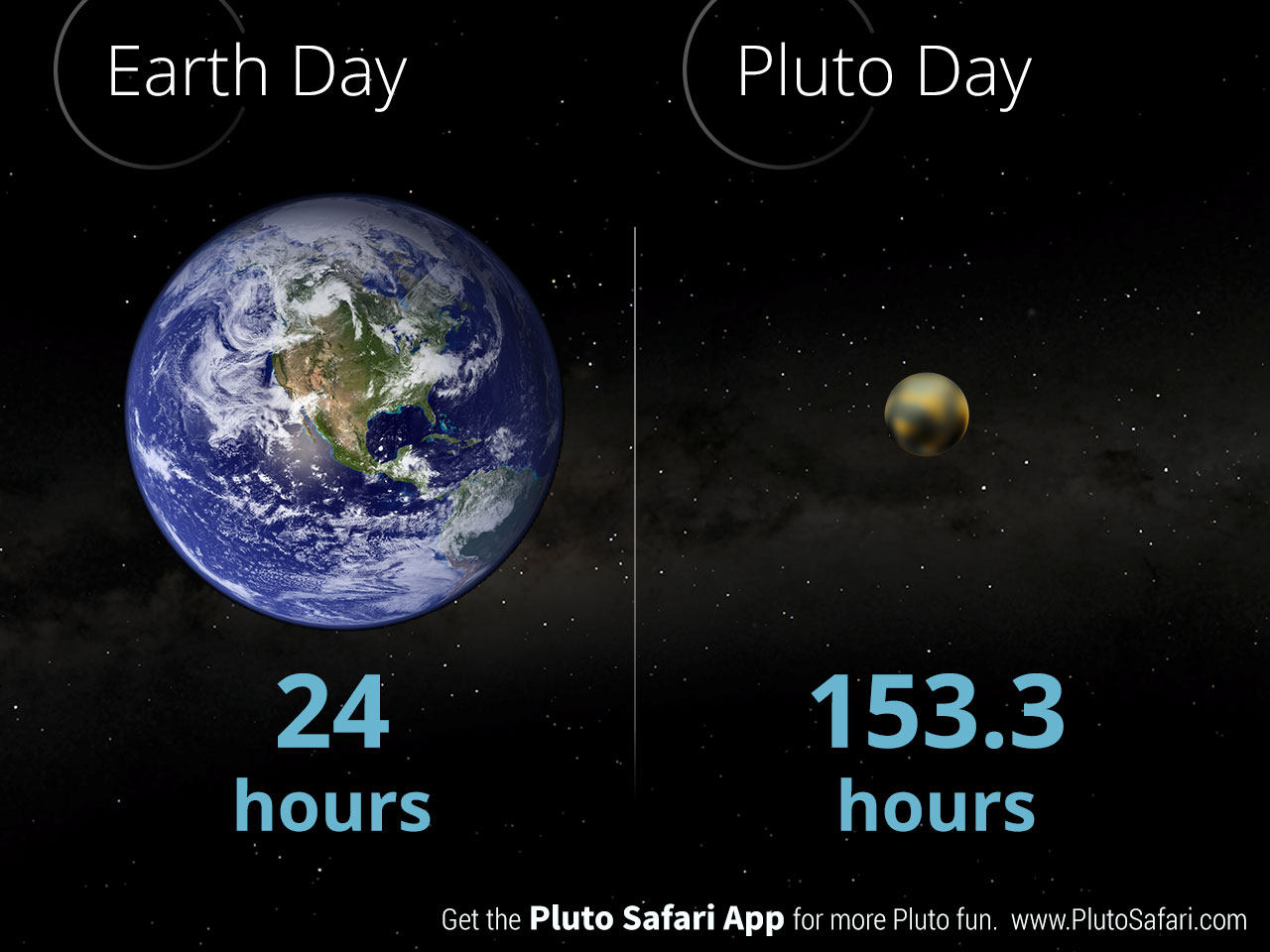

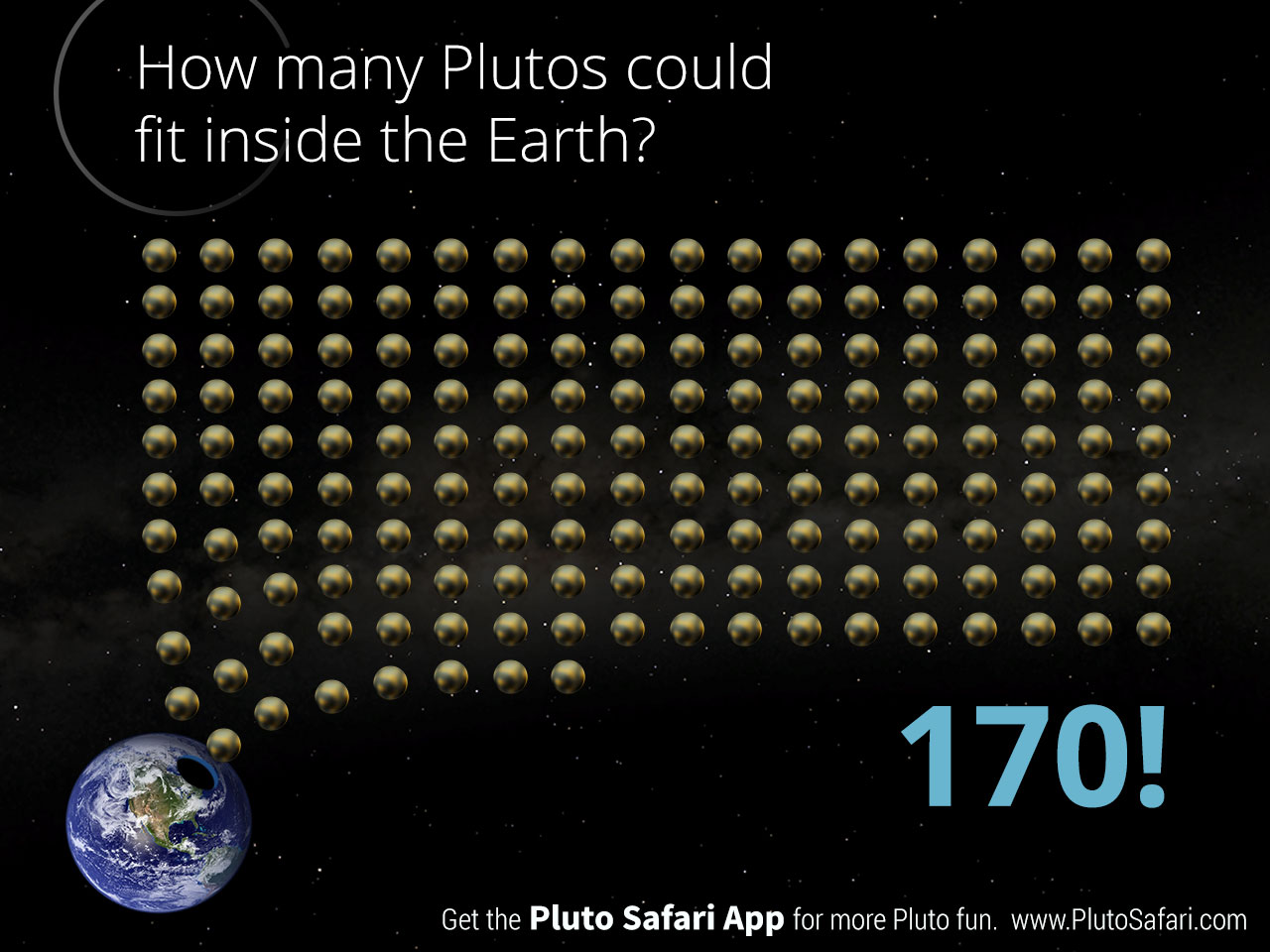

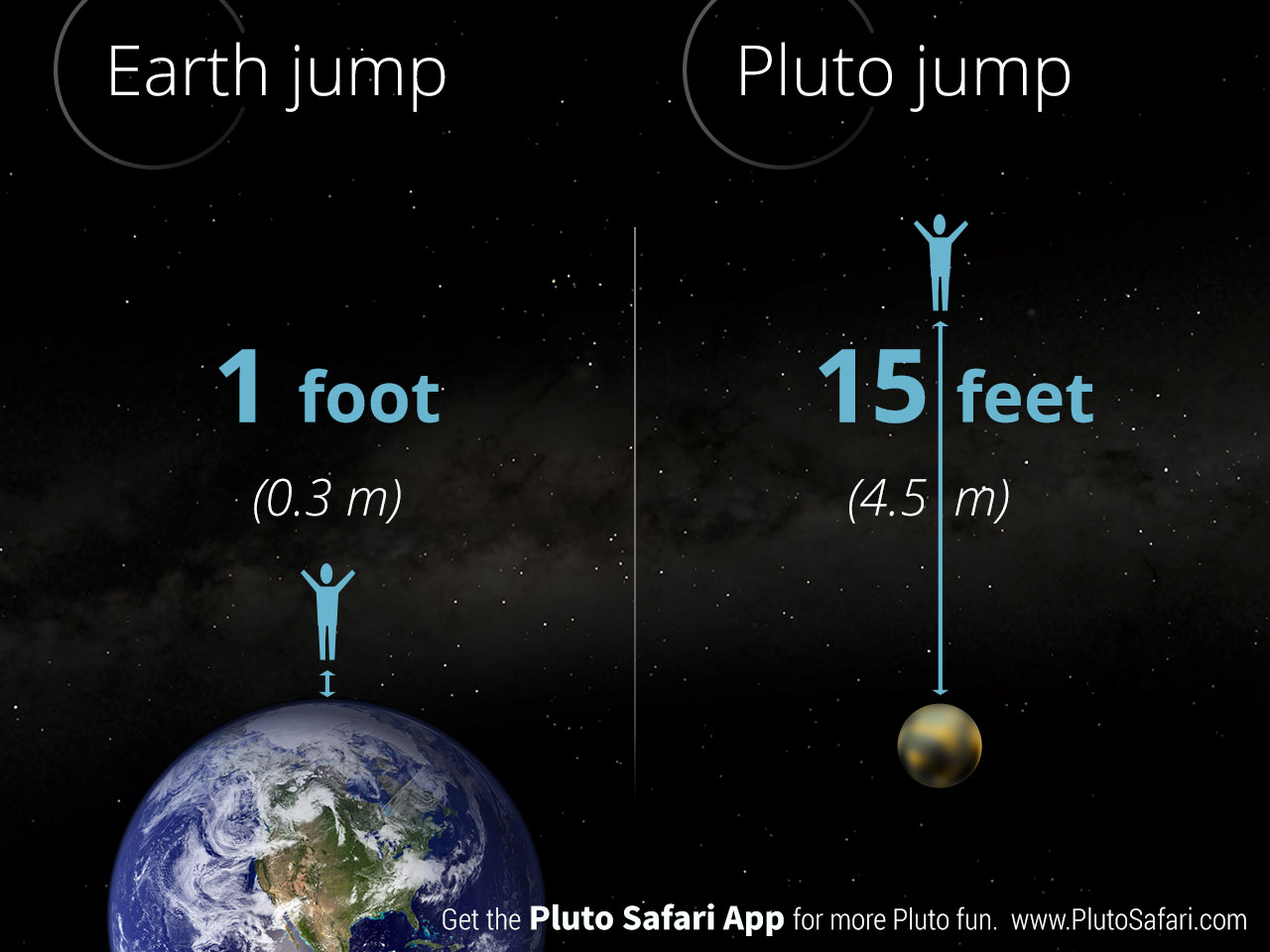

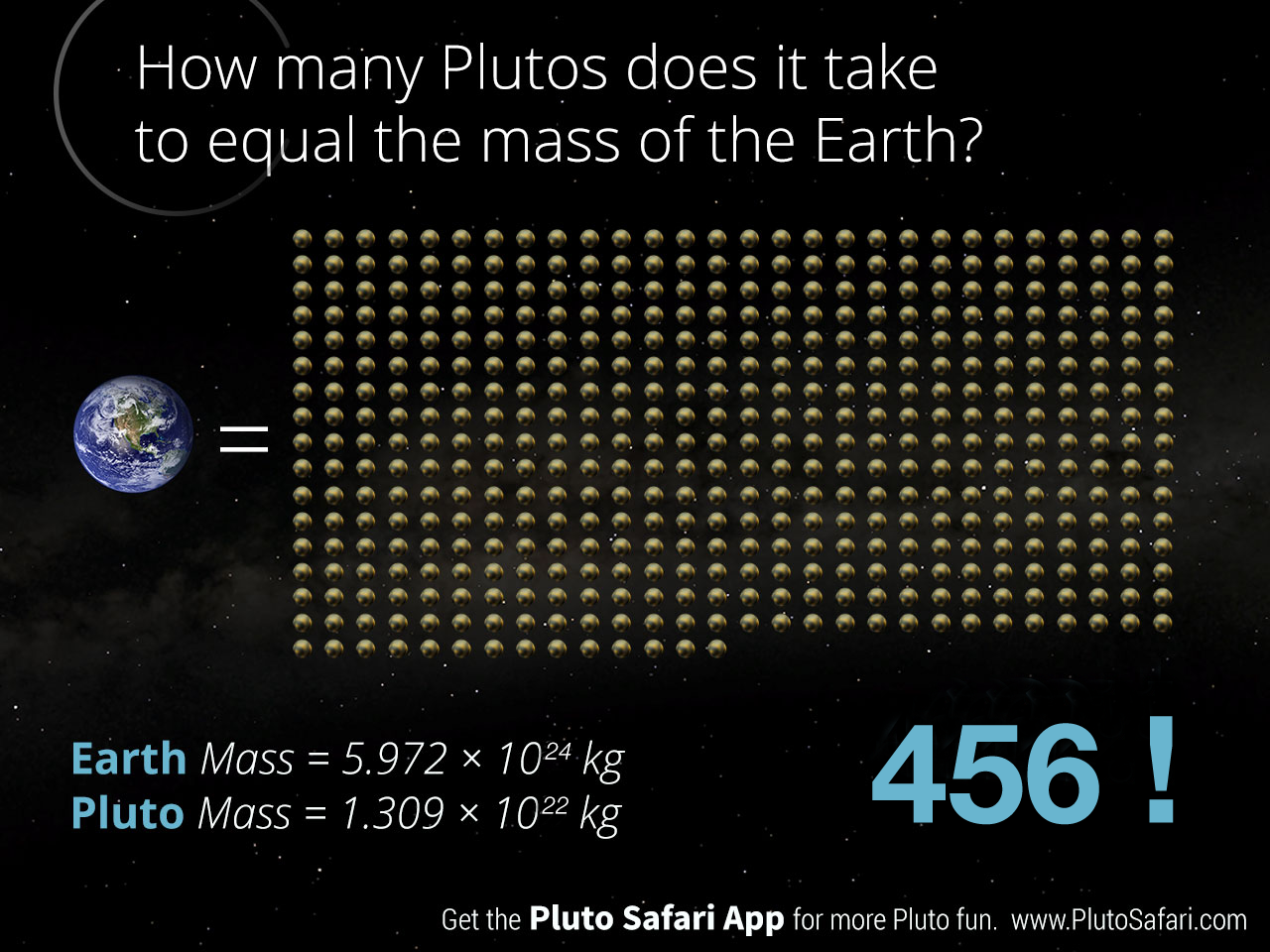

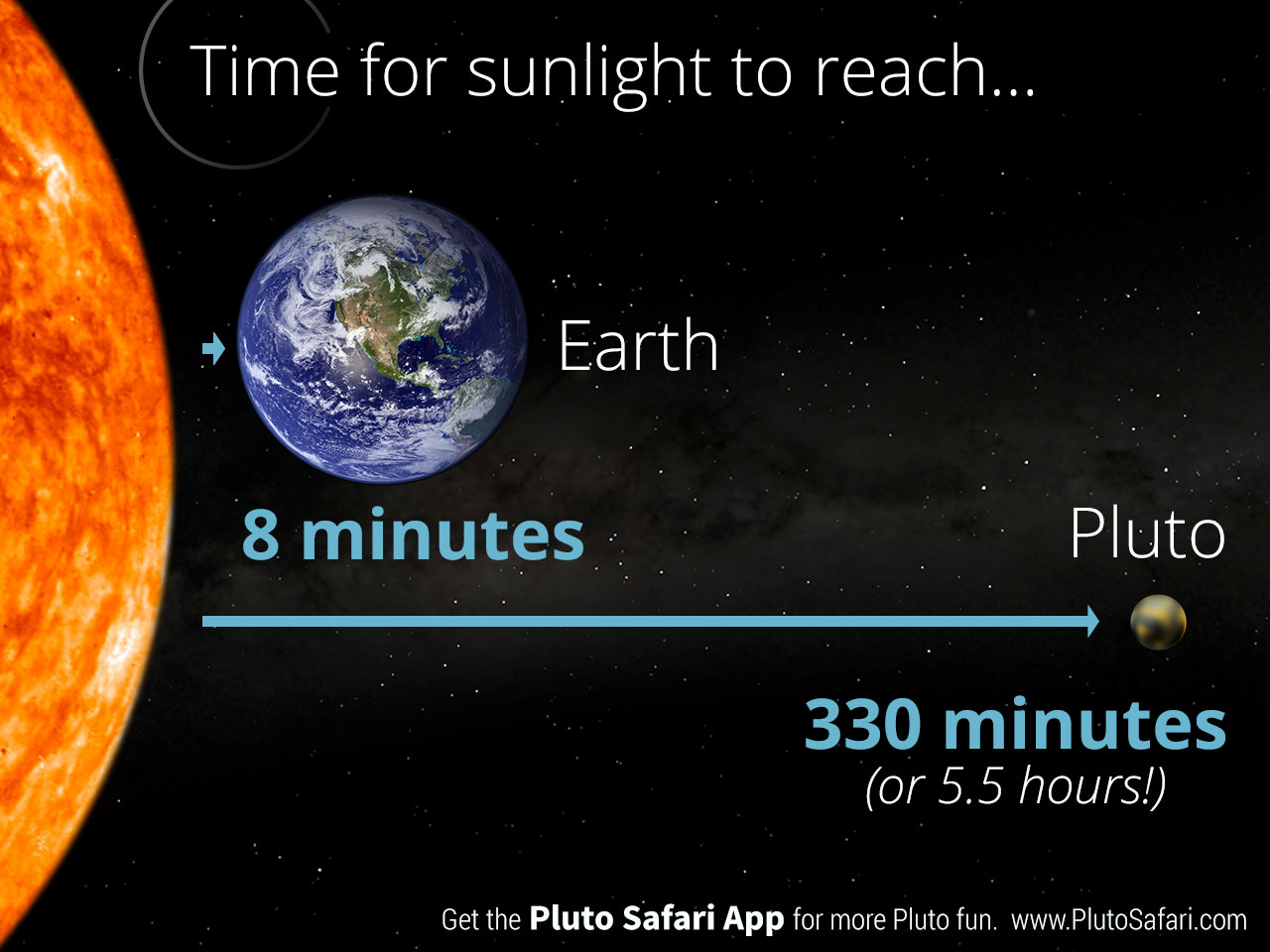

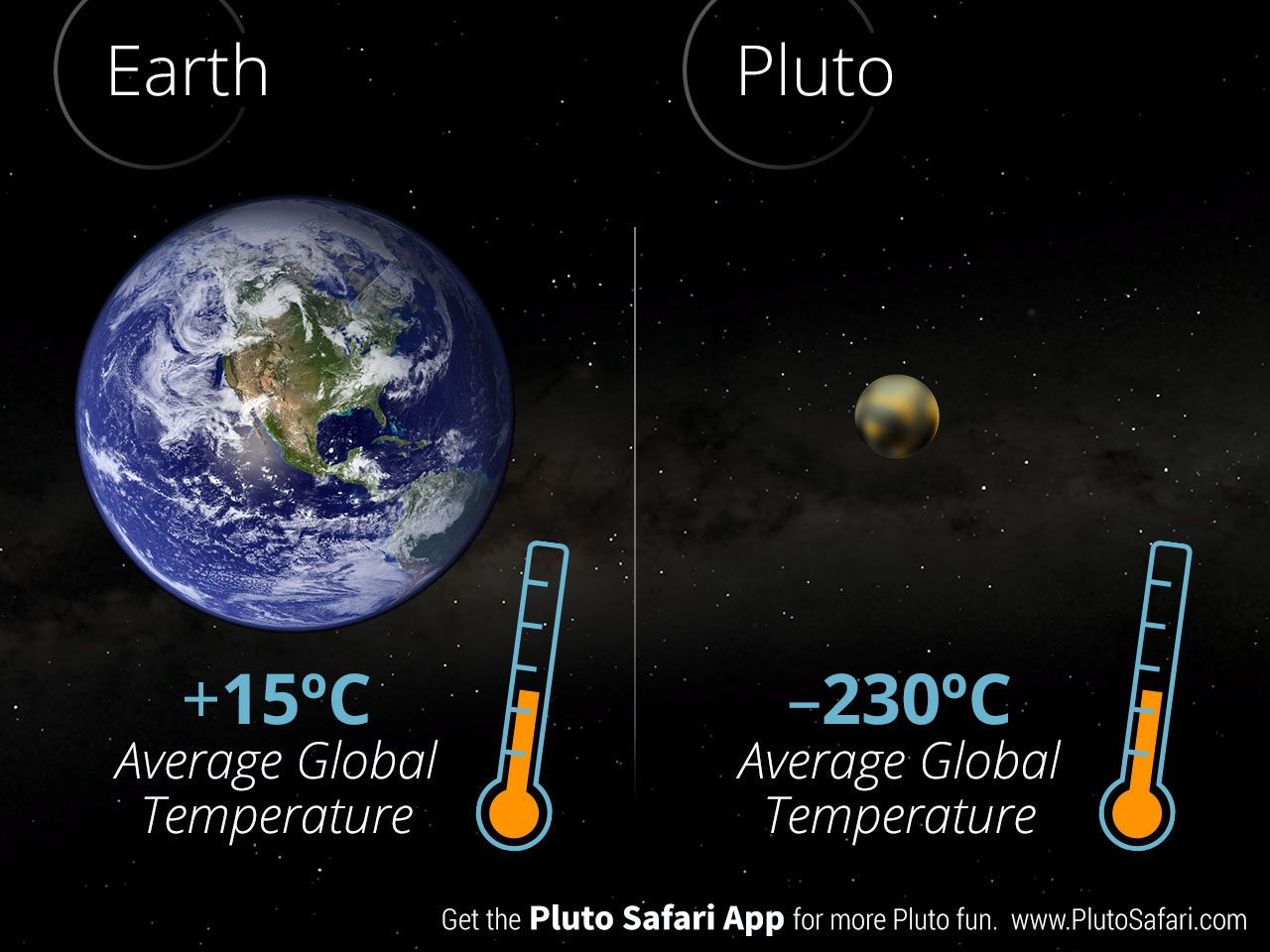

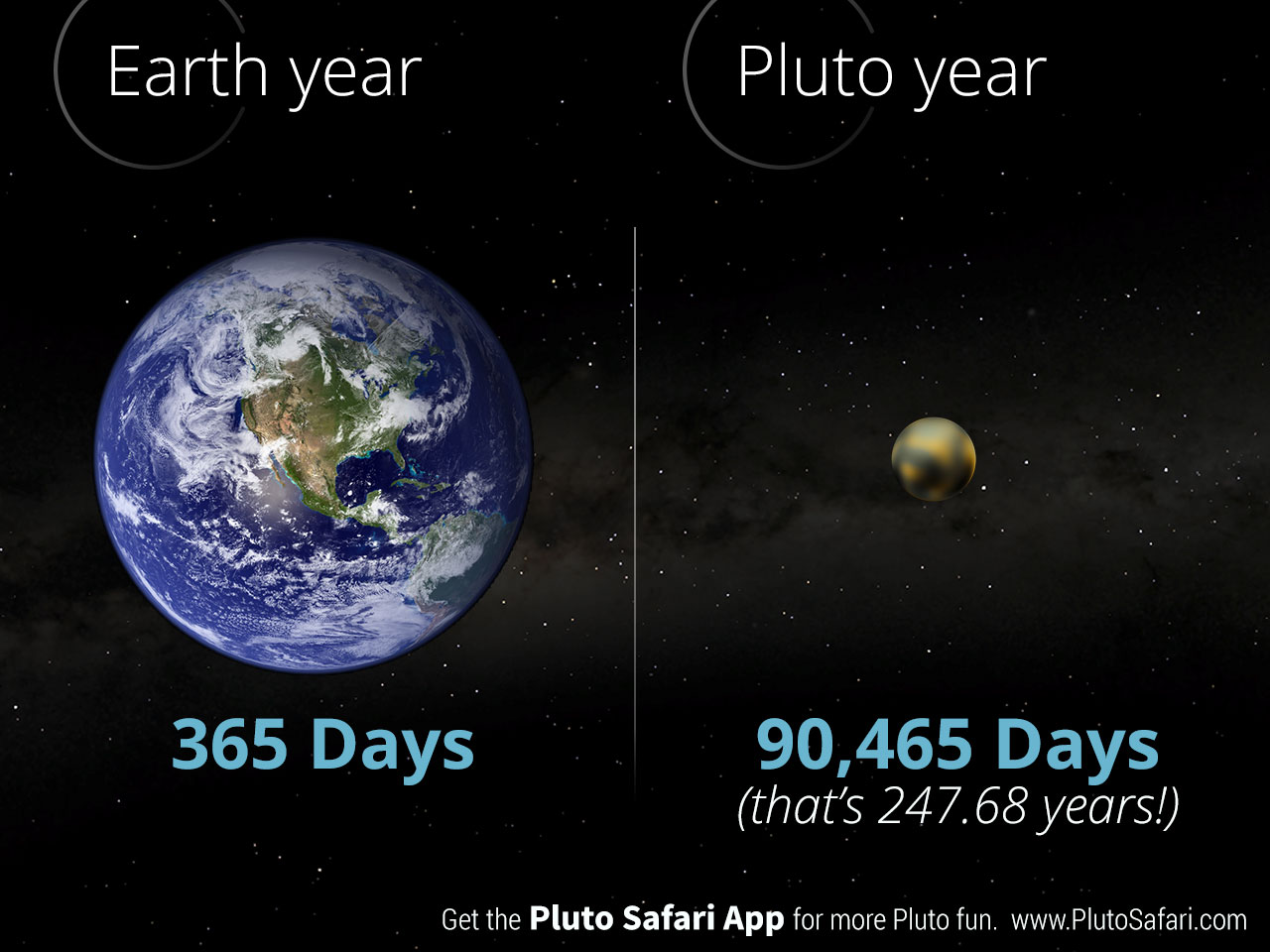

12 "Pluto Facts" Infographics